Italian Fascism and the Jews

a brief history of Jewish involvement in Italy's fascist movement

It’s commonly assumed that history has forged an exclusive tie between Jews and the Left. The reason for this has been the subject of much heated debate over the years, with explanations ranging from pure circumstance to the notion of some inborn subversiveness. This is why the strikingly disproportionate involvement of Italian Jews in the movements of Italy’s far right first caught my eye. In attempting to understand the root and nature of Jewish political activity historically and even in the present day, special attention should be paid to exceptions and counterexamples to the general assumptions that have been made. Italy is one of those counterexamples deserving of a great deal of study.

Pre-War Italy

[I]n political life, there was perhaps one significant difference between the scene in Italy and in other lands, where the Jews were mainly—except perhaps in the English speaking countries—overwhelmingly identified with the parties on the Left. Here, owing to the fact that prejudice against which they had to contend by reason of their origin was so slight, and they had first entered into prominence in public life in connection with the nationalist movement of the Risorgimento, they tended to be fairly impartially recruited from all the political factions, from one wing to other.

—Cecil Roth’s The History of the Jews of Italy, p. 476

The paramount detail for understanding the Italian context is its conspicuous lack of antisemitism. The historical consensus1, as well as the opinions of many notable contemporaries, is basically that “in Italy there is no Jewish question” to quote Dino Grandi in 1926. Mussolini was especially clear in this regard, remarking in the early 1930s that “[a]ntisemitism does not exist in Italy . . . Jewish Italians have always been good citizens and brave soldiers.” Even the less sympathetic Julius Evola would begin his Three Aspects of the Jewish Problem conceding that “[i]n Italy, there is little awareness of the Jewish problem . . . the special circumstances which have caused the most direct and thoughtless forms of anti-Semitism in some countries are not present in Italy.”

As Zimmerman (2005, 55) puts it:

When analyzing the situation in Italy, however, there is one important factor we must bear in mind: although anti-Semitic groups and leanings did exist in those years, no such overt instances of anti-Semitism occurred in Italy in the nineteenth or early twentieth centuries. Nor was Italy’s ruling class basically anti-Semitic.

Importantly, Italian Jews likewise did not recognize a problem with antisemitism in their country. From her personal research, Cristina Bettin (2007, 345) finds that “[t]he memoirs of Jewish writers born and raised in Italy during this period suggest that anti-Semitism, in its true sense, did not exist.” And externally, Jews largely viewed Italy as a miraculous oddity in the face of intense — and intensifying — European persecutions. A contemporary Jewish Telegraphic Agency article reports:

As for anti-Semitism, Italians have no conception of it. The Jews were always respected under the liberal regime . . . Sporadic efforts to transplant anti-Semitism to Italy were made at the instigation of the German Hakenkreuzler and the Hungarian Awakening Magyars, as well as followers of the notorious Professor Cuza. But none of these efforts succeeded. [Also see here]

Many reasons have been put forth as to why this was the case. Unlike other European nations, Italy was not captivated by racialist thinking, an outlook that greatly amplified existing antisemitism wherever it caught on. Perhaps Jews were also more easily integrated into the broader society owing to the fact they didn’t have a distinct language comparable to Yiddish or Ladino2.

Doubtless, the biggest factor was the tiny size of the Jewish population, which proved capable of preventing Jewish numerical dominance in virtually any arena of Italian life. According to the 1938 census, “racial Jews”3 numbered only 58,412 (some 10,380 of whom weren’t native to Italy), representing “a little fewer than 1.1 residents per thousand in Italy,” or less than 0.11% (Edallo 2021, 4).

Jews certainly punched above their weight politically, attesting to their general acceptance by non-Jewish Italians, regularly making up about 5% of the Senate and offering Europe some of the first Jewish heads of state.4 In cultural life, too: Roth (1946, 480) claims that 6.72% of biographies listed in a standard Italian “Who’s Who?” were of Jewish descent. Nonetheless, this influence still amounted to a marginal presence overall and was unlikely to be a source of ethnic conflict.

Thus, pre-War Italy offers one of the most peaceful examples of Jewish-gentile relations from the European continent, one in which a Jewish question did not arise. Whatever its causes, the major effects of this state of affairs are twofold:

Absent antisemitic barriers, the Jewish community “enthusiastically took the road to assimilation, immersing themselves into the larger Italian majority” (De Felice 2015).5 We can observe this more empirically through the proxy of intermarriage rates. Per the 1938 census, 43.7% of all Italian Jewish marriages were with a non-Jewish spouse, a rate much higher than elsewhere in Europe, and increasing (ibid.). (For comparison, this matches the trends of late 20th century America.) While Orthodox Judaism was the predominant religious affiliation for Jews, this fact suggests surprisingly many were willing to violate its age-old prohibition against intermarriage, reflecting the loosening grip of traditional Jewish particularism6. And of intermarried couples with children, 77% raised them non-Jewish (Sarfatti 2006, 28). Additionally, of the aforementioned 58,412 racial Jews in Italy in 1938, “only 46,656 had declared themselves as Jewish for the census, while the remaining 11,756 either had renounced their religion or were children of mixed marriages and did not practise the Jewish religion” (Edallo 2021, 11) — a total defection rate of over 20%.7

The lack of antisemitism removed any real stigma among Jews toward right-wing or nationalist movements which in other countries would often repel even non-identified Jews with calls to violence, if not direct exclusion. But in this case, Italian nationalism was what initially freed Jews from the ghettoes and thereafter enjoyed significant Jewish support. Mussolini himself recognized this fact, once privately remarking “Ero un ammiratore di Formiggini e non posso dimenticare che quattro dei sette fondatori del nazionalismo italiano erano ebrei” — “I was an admirer of Formiggini and I cannot forget that four of the seven founders of Italian nationalism were Jews.”8

Zimmerman (2005, 46) summarizes the condition of Italian Jewry:

The majority of Italian Jews responded to the country’s entry into war with feverish demonstrations of patriotism, filling in the shortcomings of their religious identity with the content of a national identification powerfully marked by the values and forms of the Risorgimento and an allegiance to the Savoy monarchy, which had provided equality and liberty. Participation in World War I was thus experienced as a moment of consecration in the process of Italianization, sealed by the blood shed on the field of battle. National and patriotic identification became the prevalent content of identity that restricted the space available for a Jewish identity conceived increasingly as a secondary and private religious practice.

Italian Fascism

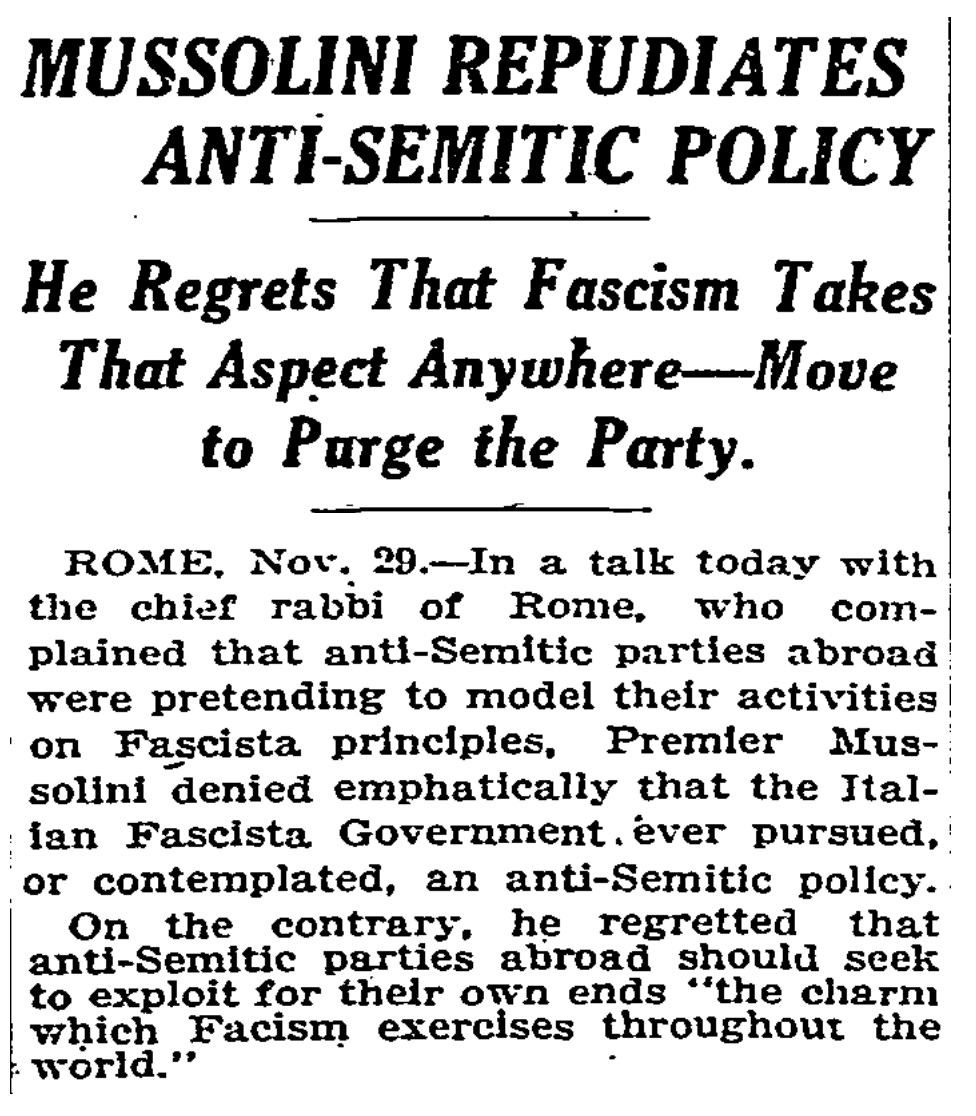

As it emerged, fascism was no different from the rest in its general respect for Italy’s Jewish community. On a number of occasions, fascist spokesmen went to great lengths to stress the friendliness of the movement toward Italian Jews.9 While his private opinions were ambivalent and self-contradictory, Mussolini was outspoken in his opposition to antisemitism, which he justified in terms of both the contributions of Jews and the strategic harm in excluding them.

As he told a Romanian newspaper in 1927 (Romania being perhaps the most antisemitic country in Europe):

Fascist anti-Semitism or anti-Semitic Fascism is an absurdity. We have been much amused by the efforts of the anti-Semites in Germany and elsewhere to associate Fascism with anti-Semitism. Fascism seeks unity; anti-Semitism seeks destruction and separation. We protest against these attempts which compromise Fascism. Anti-Semitism is a product of Barbarism to which our movement is diametrically opposed. If we are to exclude Jews, we will only strengthen our enemies

As may be expected, this attitude evoked much criticism from the other far right movements of the day, which apparently couldn’t comprehend non-hostility toward Jews as being anything other than evidence of a hidden Jewish conspiracy. According to contemporary reporting, the early National Socialists disavowed their initial “fascist” branding after finding the movement too tolerant of Jews.

Cofnas (2023) relates another example:

Adolf Dresler—the first Nazi to write a biography of Mussolini—deemed fascism a “Jewish movement, utterly dissimilar to anti-Jewish Hitlerism” (ibid., p. 37). Citing some bizarre rumors, Dresler speculated that Mussolini might be Jewish himself—an immigrant from Poland with the real name of “Mausler.” Far-right Nazis frequently smeared Mussolini as a “Jewish hireling” (Judenknecht) based on his real (and sometimes imagined) Jewish associations and supporters (ibid., p. 39).

But, as with Italy in general, this tolerance also allowed for considerable Jewish support for and overrepresentation in the fascist movement. In fact, prior to their 1938 expulsion from the PNF discussed later, Jews were somewhat more likely to be fascists than ordinary Italians: while comprising only about 1 per thousand of the overall population, their membership numbers were consistently 2–3 per thousand10. As time went on, Jewish recruitment rates reached the national average. In the 1928–1933 window, "4,920 Italian Jews joined the fascist Party, representing slightly more than 10% of the Italian Jewish population as a whole. The membership percentage of the non-Jewish population was roughly the same" (Bettin 2007, 344).

And this was even more apparent among early fascist elites.

In a room obtained by the Jewish Cesare Goldmann (Brustein 2003, 327), maybe 150 so-called sansepolcristi gathered to proclaim the foundations of fascism and form the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento (to become the PNF). Estimates vary as to the number of identified Jews and the number of total attendees, but reporting from the era identified six Jews among an official list of 105 total founders, or almost 6%. While small, the proportion of Jews in the Italian population is far smaller; if this estimate is accurate, this would constitute overrepresentation by a factor of 50. Other estimates note five Jewish attendees among a total of 100-200 people: Goldmann, Jacchia, Luzzatti, Momigliano, and Rocca (Fabre 2005, 234ff).

At times, however, this was more extreme. Bettin (2007, 343) notes that “[i]n 1925, five out of the 24 people [21%] who participated in the meeting for fascist culture in Bologna were Jews (Gino Arias, Margarita Sarfatti, Angelo Olivetti, Carlo Foà, Guido Jung),” and Brustein (2003, 327) that “[o]f the fifteen learned jurists asked by Mussolini to draft the fascist constitution, three were Jews [20%]. They were Professors Arias, Barone, and Levi.” This second fact is slightly less surprising given that at the time Jews purportedly constituted 8% of all Italian professors (Roth 1946, 480); the Jewish Giorgio del Vecchio was the first fascist rector of the University of Rome and later appointed to the PNF’s Party Directorate (JTA; Brustein 2003, 327–8).

Other notable Jewish fascists include:

Margherita Sarfatti, an editor of Gerarchia (official fascist magazine) as well as Mussolini’s mistress, private secretary, and personal biographer (Bettin 2007, 343–4; Brustein 2003, 327–8; JTA)

Aldo Finzi, Undersecretary of the Interior, member of the Grand Council of Fascism (its highest executive body), among other things (Bettin 2007, 343–44; Brustein 2003, 327–8)

Guido Jung, finance minister/cabinet member (Brustein 2003, 327–8; Brustein 2003, 327–8)

Gino Olivetti, first head of the Confindustria (Brustein 2003, 327–8)

Carlo Foà, another Jewish editor of Gerarchia (Bettin 2007, 343–44; Brustein 2003, 327–8)

Pietro Jacchia, sansepolcrista, founded the fascist movement in Trieste (Sarfatti 2017, 46ff)

Dante Almansi, vice-chief of police (Bettin 2007, 343–44; Brustein 2003, 327–8)

Maurizio Rava, vice-governor of Libya and governor of Somalia, general in the fascist militia (Bettin 2007, 343–44)

Torre, chief commissioner of Italian railways (JTA)

Renzo Ravenna, podestà (appointed mayor) of Ferrara (Bettin 2007, 343–44)

Edoardo Polacco, general secretary of the PNF in Brindisi (Brustein 2003, 327–8)

Jews were at times highly consequential to the success of the movement and the ideology itself. According to Ernst Nolte (1966, 230), “[t]he founder of Roman fascism” was none other than Enrico Rocca, the Jewish sansepolcrista noted earlier. Unfortunately, little can be gleaned from the Internet about this man — other than the fact that he was apparently so close with Mussolini such that the latter personally intervened to secure Rocca’s employment, even during the race legislation: see Davis (2021). Professor Gino Arias, on the other hand, was known to have been the leading theorist of fascist corporatism (Nolte 1966, 230).

According to Cofnas (2018), it was Margherita Sarfatti who ”urged Mussolini for months to undertake the March on Rome that led him to be appointed Prime Minister in 1922.” Around 230 Jewish fascists participated among thousands of other marchers11 who were let into the city, it was reported, by the Jewish commander of Rome's military garrison, Massimo de Castiglioni12.

Of course, Jews were simply too small a demographic in order to be as extremely (sometimes comically) influential as they have been in certain movements elsewhere, and this is probably one of the reasons why the Jewish fascists now belong to a largely unknown chapter in history. But clearly there’s enough here to constitute a significantly disproportionate role of Italian Jewry — or what might be construed under different circumstances as a “sinister Jewish hand behind fascism.”

Indeed, while Nazi smears of Italian fascism softened for practical reasons, they continued to lambaste the movement as Jewish well into the 1930s. In his book, reported on in the following article, Alfred Rosenberg depicts Mussolini as having been “besieged” by a “Jewish chain.”

The overrepresentation of Jews was certainly highest during the earlier period of Italian fascism. We can observe it gradually diminish as antisemitism in the party grew more pronounced, especially in the fascist press. Some authors13 have even suggested that there formed a deliberate restraining of Jewish representation (and perhaps visibility, in light of foreign smears) in the upper echelons of party and state.

But in reality, this kind of thing was inescapable for a right-wing movement in such a deeply antisemitic European milieu, not confined to Italian borders and Italian ideas but influenced — and more importantly threatened — by the other nations. The most imminent threat was the growing power of the Third Reich just a matter of miles to the north. The cost-benefit analysis of allying with the Reich is absurdly obvious, but one of those costs was the advent of official antisemitic policy. Most notable was the barring of racial Jews from the PNF entirely in 1938, something which “took the Jewish community by surprise, precisely because there was no such thing as a Jewish question at the time” (Bettin 2007, 345). This is also the year when the story ends.

Zimmerman (2005, 55): quoted above

De Felice (2015, ?): “There is little reason to discuss the almost complete absence of anti-Semitic motivations. . . . If there was anti-Semitism in Italy, it was limited to smaller groups that were socially outside the mainstream.”

Michaelis (1978, 3ff): “All students of Italian Jewry, whether Jewish or Gentile, Fascist or anti-Fascist, are agreed that there was virtually no Jewish problem in modern Italy.”

Roth (1946, 474): “After 1870, there was no land in either hemisphere where conditions were or could be better. . . . the Jews were accepted freely, naturally and spontaneously as members of the Italian people, on a perfect footing of equality with their neighbors.”

Zimmerman (2005, 25): “[U]nlike most other European Jews who spoke a separate language – Yiddish or Ladino – Italian Jews spoke the local dialect of the city they lived in.”

Bettin (2007, 347): ”In general, the Hebrew language was not taught and the traditional Hebrew name given to a child at birth fell out of usage as the child grew up, to be replaced by another name.“

A person was classified as racially Jewish if they had two Jewish parents, one Jewish parent who married a foreigner/unknown person, one Jewish parent while not renouncing Judaism, or if they professed Judaism even without Jewish ancestry. View the law here.

Luigi Luzzatti (1910–11) and Sidney Sonnino (1906, 1909–10) were Italian Prime Ministers. Ernesto Nathan was the mayor of the capital city Rome (1907–13).

From multiple sources (Bettin 2007, 343; Roth 1946, 479; JTA) I’ve gathered the following data points for Jews in the Italian Senate:

1901: 7/? = ?

1902: 6/350 = 2%

1919: 24/? = ?

1920: 19/350 = 5%

1923: 26/406 = 6%

1927: 17/352 = 5%

One exception to this opinion is Cristina Bettin’s “Jews in Italy between Integration and Assimilation, 1861–1938” which I use quite a bit. I can’t help but get the feeling that Bettin overly relies on anecdotal evidence in the face of what I’ve presented in order to split hairs over assimilation, acculturation, and integration.

Bettin (2007, 345): “The Reform movement, so important in Germany and Anglo-Saxon countries, struck no roots in Italy, although it was debated in the Jewish press. Italian Jews remained faithful to the Orthodox trend in the same manner that many Italians clung to Catholicism: they did not fight against tradition but neither did they respect it much. Most of the Jews in Italy were non-observant and they expressed their Judaism, up to World War II, through their family attachment that was often more a demonstration of elitism than of religious particularism, as attested in their biographies and memoirs.”

Granted, this is only in terms of religion, but the primary impetus was not to surmount few and far between antisemitic barriers but to assimilate into Italian society, accompanied with marrying a non-Jewish spouse and raising non-Jewish children. While 77% of intermarried Italian Jews raised their children Jewish, nearly all endogamous couples raised their children Jewish; both groups were obviously confronted with the same obstacles which suggests a genuine desire for assimilation.

This quote has been cited in a couple of places, including Bosworth’s Mussolini (2002, 343), but the original source is Palazzo Venezia: storia di un regime by Mussolini’s biographer, Yvon de Begnac. Who exactly these four figures are is unspecified.

Examples include:

“Fascism is Opposed to Anti-semitism, Italian Leader Emphasizes”

“Mussolini Condemns Antisemitism in Interview with Emil Ludwig”

“Italy Laughs at Reich Claim Caruso Was Jew”

“Italian Culture Chief Assails Nazi Race Policies”

In the 1930s, the fascist press gradually became more antisemitic, though the government typically denied any responsibility.

Sarfatti (2017, 7): “I have calculated the percentage of “Jews” among the total PNF membership for 1922: 2,40 per thousand, and for 1938: 2,17. . . . Having said all this, I believe we may conclude that, over the years, Italian Jews made up between 2.0 and slightly less than 3.0 per thousand of overall PNF membership. Altogether Jews were less than 1 per thousand of the population, whereas the percentage of their membership is between two and three times as high, something which needs to be analyzed.”

With such a large crowd of an unclear size, the Jewish overrepresentation here is at most 10x, but probably closer to 7x. Obviously, the larger the size of any given event, the smaller the Jewish proportion is going to be, no matter how involved they are with the overall movement.

See Brustein (2003, 327–8). Original sources can be viewed here and here.

Cecil Roth (1946, 510), e.g., points out that “[i]t was noteworthy, however, that when the Italian Academy was founded, no Jew was nominated to membership, though some were unquestionably among the leading figures in the country’s intellectual life.” As noted earlier, Jews were also 8% of Italian professors. Also see Sarfatti (2006, 16).

I don't know if Kemalism can be classified as right or left, but jews were over-represented in that faction too (both regular and Donmeh). Although, despite rumors, Ataturk was not actually secretly a jew.

Excellent