I’ve covered the myth of Judeo-Bolshevism before, concluding among other things that Jews were not nearly as overrepresented among the Bolsheviks as has been claimed. The bogeyman of the bloodthirsty, vengeful Jewish Bolshevik has long been, and continues to be, a pillar of right-wing antisemitism. It follows that its toppling is important if the Right is ever to be redirected toward reality, and away from potentially destructive and paralyzing distractions. My initial article will not be my last on this topic, and has certainly left much ground uncovered, but this should mostly be taken care of when I get around to finishing my review of The Culture of Critique’s “Jews And The Left.”

One of the great conundrums of the “the Jews did it!” theorists regarding Bolshevism — one that occurs to just about any reasonable person — is that its deadliest leader was a gentile. There are many ways antisemites will grapple with this inconvenience. Admittedly, some will acknowledge it and not feel the need for such black-and-white interpretations of history. Others, on the other hand, will allege that the premise itself is incorrect: Stalin was a crypto-Jew, or at least totally in bed with them both figuratively and literally. (See here for an example.)

I think this illustrates the intellectual-conspiratorial spectrum of antisemitism pretty well. At one pole we find perhaps understandable critiques of Jewish culture and behavior; at the other is /pol/ lunacy and borderline schizophrenia, maybe best summarized by the 2017 film Europa: The Last Battle. (See 31:41) I intend for this blog to mostly be dedicated to evaluating ideas closer to the former pole; occasionally, however, it can be useful to glance at the latter1.

Some Context

Joseph Stalin was born and baptized in Gori, Georgia. His parents were baptized Orthodox Christians and wed in Gori’s Uspensky Church. His mother encouraged Stalin to attend the local seminary, and he obliged until his expulsion and change of heart. He would marry twice: first to a Georgian and then a Russian.

Stalin’s ethnic background was mostly Georgian, but there are signs he may have been partly related to the Ossetians, a nearby culture of pagan nomads. His original surname, Jughashvili (Russified: Dzhugashvili), is Georgian in form, its ending (-shvili) meaning “son of.” The etymology of “Jugha” is decidedly less clear2, and has been the subject of much speculation over the decades, although Stalin’s father claimed it comes from the Georgian word ჯოგი (“jogi”: herd) after his grandfather’s occupational nickname.

His attitude toward Jews was never positive, although the existence and extent of his antisemitism is a contentious topic. As noted in the previous article, he did not believe the Jews constituted a legitimate national group and thought they would disappear under socialism — a typical Marxist perspective. It was under Stalin that the three Jews of the Politburo were ousted and later executed. Yet throughout his career, the Jewish Lazar Kaganovich remained one of his closest allies and confidants.

This exception to a general rule of indifference or hostility was predictably milked by World Anti-Jewry, starting with the White émigrés through the Nazis and to their ideological heirs thereafter. But sometime in the 1930s, yet another relationship seemed to further submerge Stalin in Jewish influence: the existence of a third wife, Lazar’s sister, Rosa. This was something believed at the time by fringe, antisemitic as well as mainstream sources, and the matter still causes confusion to many. The following investigates the origins of this persistent rumor, drawing from multiple sources, some of which were only available on parts of the Russian Internet.

Rosa Kaganovich

She was the sister of the above-mentioned Lazar Kaganovich, a Ukrainian Jew who became Joseph Stalin’s right-hand man, serving a number of eminent political roles including Deputy Chair of the Soviet Council of Ministers, First Secretary of the Ukrainian Communist Party, and long-time member of the CPSU’s Politburo. At some point in the 1930s, Rosa became the third wife of Stalin, and Lazar his brother-in-law from then on.

Or such is how the tale normally goes.

In truth, Rosa Kaganovich probably never even existed. Her story is primarily about the propagation of an old myth, but one that was surprisingly widespread in the mid-20th century and taken seriously by numerous mainstream publications, certain historians, the Nazis, and even the CIA.

Wikipedia has helpfully compiled a number of examples from the mainstream press to illustrate the point, the most recent being The New York Times in 1991 (last):

The rumor was so pervasive that even Leon Trotsky had reason to believe in it. He writes in his unfinished book, Stalin: An Appraisal of the Man and His Influence, that

Stalin married the sister of Kaganovich, thereby presenting the latter with hopes for a prominent future. The marriage apparently did not last long. At any rate, nothing more was heard about it afterwards.

But as can be divined from the wording, Trotsky was relying just as much on hearsay as everyone else. He had been removed from the Politburo in 1926 and expelled from the Soviet Union a couple years later, well before the supposed marriage took place.

Yet another contemporary account is to be found in Face of a Victim3, the 1950s testimony of a Soviet defector by the name of Elizabeth Lermolo — although she, too, received all her information second- or third-hand. Lermolo describes “Roza” as a femme fatale, or perhaps belle juive, whose affair with Stalin is what ultimately led to his wife Nadezhda’s death.

Some time prior to this episode with Zoya, a new figure had appeared on the Kremlin stage in the person of Roza, the sister of Lazar Kaganovich, member of the Politburo. Roza was a dashing brunette of about twenty-five, witty and sophisticated, so striking in looks that even Nadya seemed plain and unattractive by comparison. Whether of her own volition or at the behest of her brothers, she had turned her charms on Stalin and conquered him completely. He was a frequent visitor at the Kaganoviches' home at Silver Pines in the summer of 1932. (Lermolo 1955, 226)

The story was revamped with the writing of Stuart Kahan’s The Wolf of the Kremlin in 1987, a narrative biography of Lazar alleging a great deal of shocking insider information. It also takes for granted the existence of his sister Rosa, Stalin’s wife, personal doctor, and, at the behest of the Politburo, poisoner. The book was a modest success, even being cited in The Culture of Critique (xxxviii; 2002 ed.) as Kevin MacDonald uses it to paint Bolshevik terror in the light of homicidal Jewish vengeance.

The Kaganovich family caught wind of Kahan’s volume upon publication and issued a prompt reply refuting just about all of its claims. About Rosa, they state Lazar had just one sister by the name of Rachel who died back in 1926. Lazar himself, who was still alive, denied that Kahan was his nephew4 or had ever held a meeting with him, and had always maintained he had no immediate relative by the name of Rosa.5

His daughter has written the following on a separate occasion:

[T]he book “The Wolf of the Kremlin” by the American journalist S. Kagan [Kahan], who, having declared himself a nephew, pulled out a whole bunch of slanderous fabrications. Suffice it to say about the fiction of a certain mythical sister, Rosa, who never existed. The only sister of L.M. Kaganovich, Rakhil, lived all her life with her husband and six children in Chernobyl and died in 1926 in Kyiv, where she was buried. [rough translation of the Russian]

And the Kaganoviches aren’t alone in their position. On the other side, Stalin’s only daughter, Svetlana, categorically denied the rumor in her book Only One Year:

Nothing could be more unlikely than the story spread in the West about "Stalin's third wife"—the mythical Rosa Kaganovich. Aside from the fact that I never saw any "Rosa" in the Kaganovich family, the idea that this legendary Rosa, an intellectual woman (according to the Western version, a doctor), and above all a Jewess, could have captured my father's fancy shows how totally ignorant people were of his true nature; such a possibility was absolutely excluded from his life. In general, according to my aunts, he paid little attention to women, not going beyond expressing his approval of the singer Davydova, a performer of Russian folk songs. He never reacted to aggressive women who tried to arouse his interest.

Oddly enough, in the West they stubbornly tried to relate us to the Kaganovich family. To my astonishment, I learned from the German magazine Stern that I had been married to "Kaganovich's son"—to my astonishment inasmuch as Kaganovich had no son. I actually had been friends with his daughter [Maya], and the adopted boy in the family was ten years younger than I; he, when he grew up, married a girl student of his own age.

Likewise, Stalin’s son, Yakov, denied the claim even when captured and interrogated by the Nazis. In the interrogation protocols we read the following exchange6:

“You know, don’t you, that your father’s second wife [more commonly, third] was Jewish? Because Kaganovich is a Jew, isn’t he?”

“Nothing of the sort. She [Nadezhda] was Russian. What are you talking about? Nothing like that ever happened. His first wife was Georgian and his second was Russian, and that’s all there is to it.”

“Wasn’t his second wife’s name Kaganovich?”

“No, no, that’s just rumors, nonsense! . . . His wife died . . . Alliluyeva. She was Russian. He’s sixty-two now. He was married. Now he isn’t.”

(Radzinsky 2011, 477–8; my insertions)

Apparent photos of Rosa have circulated since the very beginning, and continue to be passed around on the Internet as “evidence” by those who cling to the myth. The photo depicted below is probably most common:

As we read from the caption, this is a 1939 photo of Stalin and his (young and beautiful?) Jewish bride. The source is a 1953 issue of the Illustrated London News.7

I managed to find that this photo was in fact taken in 1930, at a time when Stalin’s second wife was very much still alive (NYT).

I can’t identify who the woman sitting beside Stalin is with complete certainty, but Sirgei Kirov appears to be putting his arm around her back, suggesting she was his wife, Maria Lvovna Markus; the looks seem to match, at least.

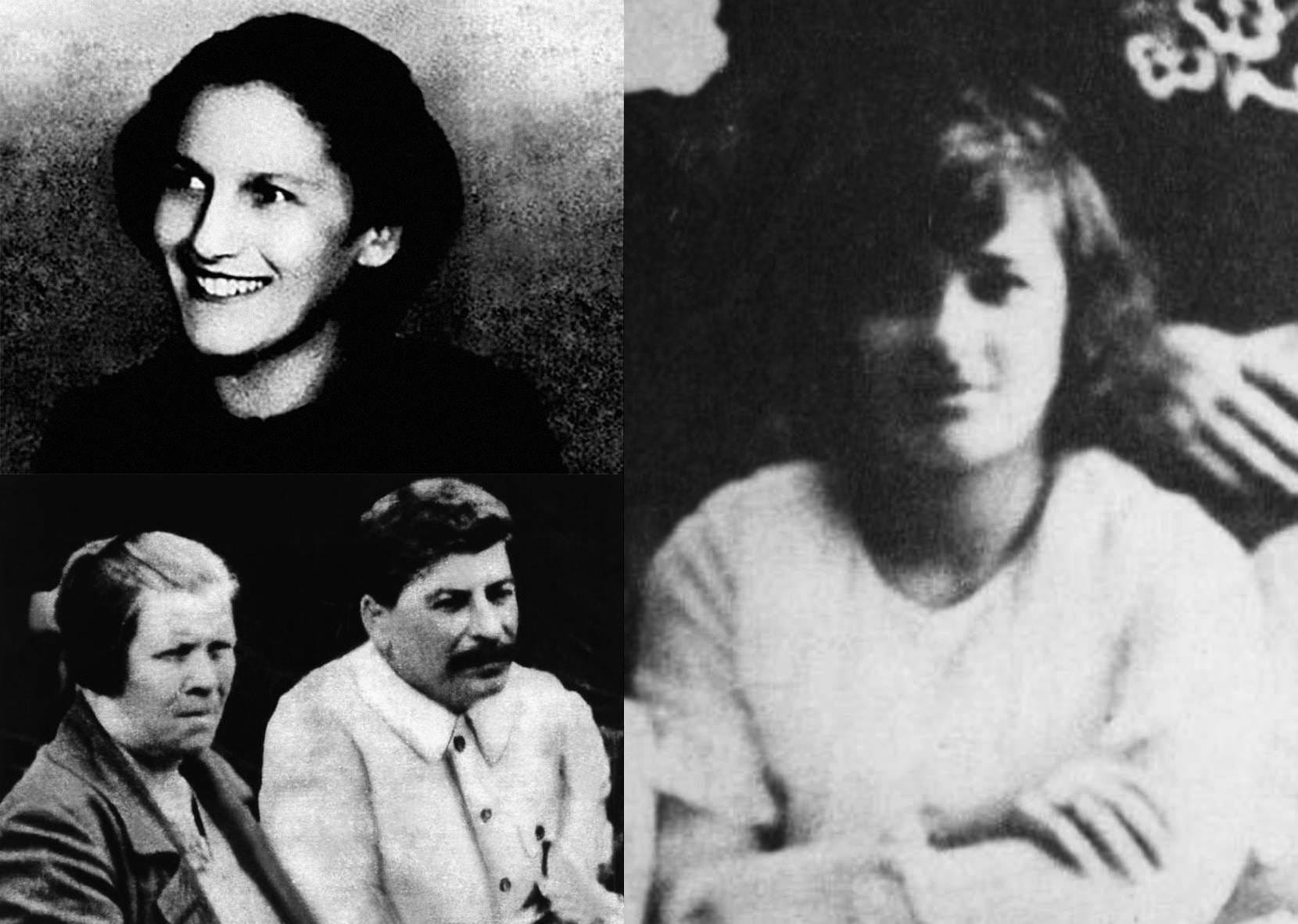

The Illustrated was not the origin of this misattributed photo, however. The following are the pages of a German magazine from the 1940s:

The photo on the bottom left also purports to be Rosa (and is still occasionally spread around online), despite looking nothing like the woman on the right. (The age difference between the two is said to be only six years, albeit I’m sure life with Stalin could be rough…)

A third photo comes from The Wolf of the Kremlin:

The date it was allegedly taken places Rosa’s age at maybe 30 when she married Stalin. While it’s impossible to trace, I’d note a striking resemblance to Lazar’s daughter, Maya, seen here. Kahan claimed to have taken the photo from Lazar’s desk (after breaking into his house, according to the latter). If true, this probably makes more sense for a photo of one’s daughter.

The precise origin of the Rosa legend is uncertain.

Some have naturally suggested that it was Nazi propaganda crafted to further their ideological narratives, but this would not explain why Nazi captors were intent on interrogating Stalin’s son regarding the woman. Indeed, while still exploiting it as valuable propaganda, the Nazis themselves took the rumor more seriously than most.

As far as I am aware, the lone scholar to thoroughly investigate this mystery has been Alexandra Arkhipova, who pieces together a convincing case through the extensive use of contemporary White émigré sources, private correspondence, and NKVD internal reports on counterrevolutionary sentiment. Accounts of her research are made available here and here, in Russian, and will be quoted from below.

Arkhipova traces it back to the White émigré press which continued in exile the White Army’s task of slandering Bolshevism as Jewish8. Originally, such antisemitism centered around the sinister influence of “Trotsky-Bronstein,” and to a lesser extent the other powerful Jews like him: Zinoviev, Kamenev, Sverdlov, etc. But by the mid-1920s, these people had been ousted from power by Stalin and later killed or exiled (or both). This episode, along with subsequent expressions of perceived Stalinist antisemitism, created a lasting impression among some antisemites that Stalin was resisting a “Jewish yoke” within the system of communism. Yet, of course, the urge simultaneously arises to portray even Stalinism as Jewish, being the deadliest period of Soviet rule and what the Nazis were so heroically battling in WWII.9

Eyebrows were raised when Lazar Kaganovich was promoted to full Politburo membership in 1930, despite the fact that he had always been an antisemite by his own admission, having no real loyalties except to Stalin. (It’s known he had effectively approved of Stalin’s execution of his own brother.) According to Nikita Kruschev, a “Jew himself, Kaganovich was against the Jews!” — something Lazar himself basically rephrased in a deathbed interview:

Even today, during the time of the collapse of our state, they [Jews] are in the first ranks of those who instigate public disorder. Before the war, we successfully overcame the heritage of Jewish bourgeois nationalism, but after the war they forgot who saved them from destruction by Hitler. We carried out an offensive against cosmopolitanism and struck first of all at the Jewish intelligentsia, the primary army of the cosmopolitans. . . . This is by birth only. In general, I never felt myself to be a Jew. I have a totally different mind-set. Unlike the Jews, who are prone to anarchy, I love order.

Evidently, Lazar himself proved not catchy enough for the antisemitic presses. There just had to be something even more damning…

Arkhipova finds an “R. M. Kaganovich” in lists of high-level Soviets distributed around the scene, a possible typo interpreted thereafter as referring to “Rosa Moiseevna Kaganovich.” Such is probably all it took for the thing to catch on; by 1935, the first major references to Lazar Kaganovich’s sister are found, though she wasn’t yet connected to Stalin. Like a rolling snowball, baseless speculation was added to the mix as fact, and the story branched into a thousand contradictory interpretations. (It also didn’t help that Western journalists were desperate for news from the ultra-secretive USSR.)

Originally Rosa was a musician, but eventually she became a doctor. Originally she was much older than Stalin, but more popularly she was a young woman (~25 per Lermolo). In some accounts she was the reason for Nadezhda’s jealous suicide, in others her poisoner, and in still others she was a mate arranged for Stalin after the fact entirely. She was said to have killed Stalin for his antisemitism, or (in Kahan’s case among others) to have been compelled to do so by the Politburo. She was said to have been killed by Zhukov afterward, and to have had a simultaneous affair with Kruschev.

During the Red Scare frenzy, things got even more careless:

After the war, a huge number of memoirs appeared, written by former citizens of the Soviet Union. Sometimes it was the only way to make money. Memoirs were written by people who had nothing to do with the Soviet government and knew nothing about the history of the country. Therefore, texts of this kind often appeared: I was Stalin's nurse (the story is that Stalin actually lives in a wheelchair), I was a cleaner in the Kremlin, I was Stalin's cook, and so on. And all these people have only one thing in common: they often mention Rosa Kaganovich.

Trying to keep in mind all the different Rosa Kaganoviches is a dizzying task. Even her name has been given variously as Rosa/Roza, Sarah, and even Mary, her middle name being either Moiseevna, Lazarevna, or Mikhailovna. In most versions she was Lazar’s sister, but in some she was his daughter or niece.

According to the Soviet defector and Trotskyite Alexander Barmine, she was his daughter:

“Shortly after Nadia's death, we learned that Stalin had married Kaganovich's daughter. But so far there is no information about this marriage,” wrote Alexander Barmine, a well-known Trotskyist who served as a diplomat in different countries, and then fled the USSR. Arriving in Paris, Barmine decided to do what all Russian emigrants who found themselves there did: write memoirs. He finished the first draft of the manuscript, but its readers, including possibly Trotsky himself, said the book was too boring. Then, in Barmine's book, an inserted chapter appeared about Stalin's sixth finger, his secret Jewish wife, and other “details” that enliven the text.

Barmine is quite plausibly where Trotsky got the story, although, as we’ve seen, Trotsky’s version is an unnamed sister of Lazar who was married for only a short while.

An Austrian journalist declares in the 1930s that Rosa, “Kaganovich’s older sister,” was the bride in a marriage arranged by the Politburo, initiating that whole rumor. Lazar Kaganovich did actually have an older sister, Rachel, as we saw earlier; and, according to Arkhipova, the name “Rachel” (or “Rakhil”) was often replaced with “Rosa” by Jewish women in that setting. But again, Rachel Kaganovich died back in 1926, so it couldn’t have been her.

Often mentioned in addition is Lazar’s niece, Rachel, and from the Kaganovich family’s memorandum, we actually see two nieces listed as signatories: “Rachel J. Kaganovich (1918-1994),” and “Rosa I. Kaganovich (b. 1919).” So one potential Rosa and one actual Rosa, born around the same time. At the time of Nadezhda’s death in 1932, they would’ve been 12–14; this wouldn’t be the first time Stalin’s taken a liking to such an age, but it still doesn’t fit with the stories typically spread.

Or could it have been Rosa Rutman (née Kaganovich), Lazar’s aunt? With the aforementioned niece, Rutman is apparently the only other Rosa in the immediate family tree. Yet she was also in her fifties when Stalin became a widower — a year his junior and ten years Lazar’s senior — and with five children by a different man. This possibility, too, is far-fetched10. And we’ve already seen that Stalin’s and Nadezhda’s own daughter denied having seen any Rosa in the Kaganovich family at all, long after her father’s death.

The most recent account of Rosa should be mentioned — the only one to give me some pause — coming from the son of Lavrentiy Beria, Sergo. In his 1994 My Father: Lavrentiy Beria (p. 72), Sergo demonstrates awareness of the rumors about Rosa and adds something intriguing:

The same can be said about another assertion of Hitler's propaganda, that Lazar Kaganovich's sister Rosa was Stalin's wife. . . .

Then the Germans decided to play on anti-Semitism. Kaganovich's sister or niece was not really Joseph Vissarionovich's [Stalin’s] wife, but she had a child with Stalin.

She herself was a very beautiful and very intelligent woman and, as far as I know, Stalin liked their closeness and it became the direct cause of the suicide of Nadezhda Alliluyeva, the wife of Joseph Vissarionovich...

I knew the child who grew up in the Kaganovich family well. The boy's name was Yura [Yuri, sometimes Yuriy]. I remember asking Kaganovich's daughter:

“Is this your brother?”

She was confused and didn't know what to say.

The boy looked very much like a Georgian. His mother went somewhere, and he stayed to live in the Kaganovich family. How his fate turned out after 1953, I do not know.

In this account, an unnamed “sister or niece” had a child with Stalin, with the insinuation that said child was Yuriy Kaganovich. His memory seems to have cleared up by the 2001 English edition:

Kaganovich had an adopted son [confirmed adopted by Svetlana above], an Eastern-looking boy who could have passed for Jew or Georgian. My mother and I thought he was his natural son. My father revealed to us that Kaganovich had acted as go-between in a relationship between his niece and Stalin and that the little boy was actually the son of Stalin and the niece, who, I must admit, was very pretty. I found his daughter Maya no less attractive. She resembled Liz Taylor, though her curves were less generous.

By now Ms. Kaganovich has become surely Lazar’s niece, and the author recalls a memory of his father assuring him that Yuri was Stalin’s child with her, despite being unsure of his origin just seven years earlier. Whatever the case, this narrative also conflicts with the facts in important ways: Yuriy Kaganovich was born in 1931, the year before Nadezhda’s death, meaning Sergo is dating Rosa to a time when both nieces of Kaganovich would’ve been hardly pubescent — all while describing her as a “woman.” This would not be the only criticism Sergo Beria has received for his confabulations.

Fin

At present, Rosa Kaganovich has mostly been forgotten. Among the historians in the know, however, the general consensus is that she was an antisemitic myth, and that Stalin’s relationship with Lazar was forged by politics and friendship alone. Such little solid evidence and such obvious propagandistic utility, in addition to unanimous denial by the most privy parties, virtually preclude the possibility.

I do not expect this conclusion to satisfy those who continue to rant about “all three of Stalin’s wives” being Jewish, but the story offers an interesting glimpse into the long-established world of antisemitic propaganda. Hopefully this research will also prove helpful to those already familiar with the subject and seeking greater clarity.

Reviewing much wartime Nazi propaganda, I’ve realized that apparently this stuff can emerge into the mainstream and become widely believed. Not everyone is rational enough to see right through obvious myths, and when it comes down to it this is likely a far greater portion of the population than I’d like to believe. Right now, in a much different milieu, they’re relegated to gullible conspiracy theorists and thus easy to dismiss.

The bottom-of-the-barrel spergs will claim it means “son of a Jew,” most often because of the phonetic similarity between “Jugha” and “Jew… gah?” This is a fuller explanation of Jughashvili’s etymology, and this is even more contextual; written by a Holocaust revisionist, it nonetheless concludes the name has no connection to any word for “Jew.”

Stuart Kahan’s (and his father’s) claims of direct familial relationship to Lazar are contradicted by genealogical research: compare Jacob Daniel Kahan’s family tree with Lazar Kaganovich’s family tree.

“Kahan,” which is occasionally transliterated into English as “Kagan,” isn’t an uncommon Eastern Jewish surname and derives from a word for priest or “Cohen.” (The “-vich,” sometimes “-vitch,” often added on to Kahan/Kagan is a typical Slavic patronymic suffix meaning “son of.”) It follows that you can find many people of Jewish descent with these names who bear no direct relationship to the Kaganovich, try as some might to make the connection.

From the statement: “The author of the book falsely claims to be LMK's grand-nephew and makes an attempt to persuade the readers to trust his writings. In fact, he is an adventurer and neither LMK himself, nor we ever had any idea about his existence. On May 31, 1981 LMK sent a letter to A.A. Gromyko (who was at that time the USSR Foreign Minister) with a request to protect him against Stuart Kahan's pressing attempts to visit him (through the USSR Embassy in Washington). LMK vigorously denied the existence of any nephew in the USA. He wrote that he had not and would not ever receive him.”

From researcher Alexandra Arkhipova: “Kaganovich lived a long time and throughout the second half of his life he desperately argued that he had neither a sister nor a daughter, Roza Kaganovich. In 1987, a man named Stuart Kagan came to Moscow and introduced himself as Kaganovich's nephew. . . . Kaganovich denied the fact of their conversation and wrote a complaint to the Foreign Ministry that a man who called himself his nephew tried to break into his apartment. According to him, Kaganovich did not let the stranger into the apartment and now asks to protect him from the visits of strange people.”

This cognitive dissonance still remains among many antisemites. For instance, the “MYTHOS” episode of the neo-Nazi cartoon Mürdoch Mürdoch portrays Stalin as having overthrown the Jews (3:24), while immediately after depicting the Soviet foe as Jewish.

Rosa Rutman is mentioned here, as well as in this genealogical discussion of the Kaganoviches with someone personally acquainted with them and related by marriage. The full Kaganovich family tree can be viewed here.

Interesting article. I've read a lot of antisemitic literature and have come across mentions of this mysterious jewish with many times (mostly in books written by americans in the 1940's onward). Never bothered to look it up. Always assumed she probably wasn't jewish. never considered she didn't even exist.

Also, is the extent of Stalin's antisemitism really that contentious? the evidence for it seems pretty solid.

Fascinating piece. Why didn't you DM it to me!!??