So Who Killed Mary Phagan?

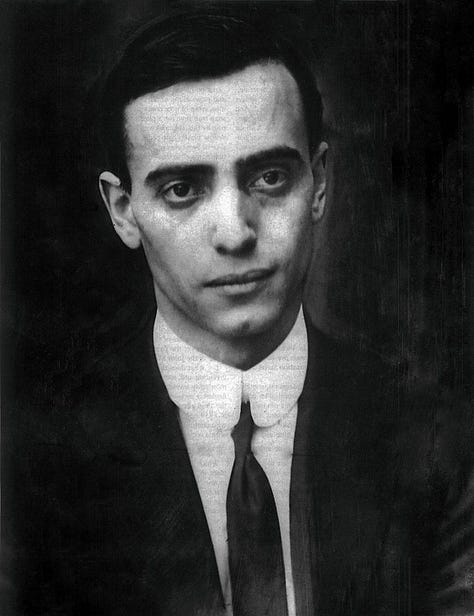

The mind-numbingly obvious culprit was not Leo M. Frank: some words

Defending Leo Frank can be a dangerous thing to do. If you spend any time online these days, his guilt can feel like consensus; simply calling it into question quickly gets one branded things like “pedophile apologist.” Of course this would only be true if Frank actually committed the crime attributed to him, and the charge can work in both directions: if he was, in reality, innocent, then it’s those claiming otherwise who are actually protecting the murderer of Mary Phagan all these years later.

Indeed it often seems the people most passionate in their reproach toward historical inquiry know the least about the case on a basic, factual level. At least that would explain all the patent lies and inaccuracies that have become integral parts of the popular narrative on the Internet. In a previous article I noted Candace Owens’ description of Jim Conley, the more likely perpetrator, as a “poor black illiterate janitor” and that seems to be the refrain. When Jonathan Greenblatt and the ADL were slapped with Community Notes for their posts on the 108th anniversary of Frank’s lynching, the same point was made.1

Conley, who initially professed illiteracy, broke down after being presented with evidence of his own handwriting and confessed to the police, “White folks, I’m a liar.” This same handwriting was moreover found to be identical to that of the infamous “murder notes” left under Mary Phagan’s corpse, which decisively tied Conley to the crime and forced him to eventually argue he’d simply written them at Frank’s dictation—an absurd, blatantly post hoc suggestion but one still parroted by his defenders to this day. Anyone using the adjective “illiterate,” even in passing, thus reveals they lack knowledge of even the basic premises of the whole affair.

Another seemingly common lie found in the Community Note is that “a half jewish half white Southern jury” convicted Frank, implying I suppose that even some Jews were forced to throw their hands up and conclude Frank did it. There were four Jewish members of the grand jury that indicted him, still far from half. Yet not only does support for an indictment in no way demand a belief in one’s guilt, we have no idea how these Jews voted because it was only the trial jury which would later convict that required unanimous decisions. And not one of the members of that body was Jewish.

Further, if she’s not being described as a “white girl” as per the Note, frequent reference is made to Mary Phagan as a “young Catholic girl,” her Catholicism holding some sort of narrative significance. For Candace Owens—who literally thinks the Frank case was an instance of Jewish ritual murder, mind you—this plays into delusions of a special Jewish hatred for the One True Church. But Mary’s family was not in fact Catholic and her funeral was held in Marietta’s Second Baptist Church.2 (Candace’s promise that “Catholics will never allow them to bury what was done to you” is made even more preposterous when one realizes Mary’s most vocal defenders from Tom Watson to the Klan have all been staunchly anti-Catholic.) Clearly, at least in many cases, the indignation of the anti-Frank types greatly exceeds their grasp of the history, which I think deserves a fair hearing. They’re surely aware of the presence of dissenting voices, but those come from historians with Early Lifes that don’t even need checking and whose works they’d much less care to actually read.

One would obviously be right to suspect they don’t actually care about Little Mary Phagan, either, despite all the crocodile tears. For them the Frank case has a few uses, and not merely to discredit all subsequent activities of the Anti-Defamation League which sprung up in its wake and which I’m not inclined to defend anyway. It represents a microcosm for both Jewish sadism—in Frank’s victimization of the gentile girl—and ruthless clannishness—in their univocal defense of a pedophile-murderer-esoteric blood cultist simply out of tribal instinct—providing almost a gateway drug into the larger world of the “Jewish Question” for those who simply dislike the ADL. The total absence of such communal defenses for later co-ethnics like Jeffrey Epstein or Harvey Weinstein, let alone Julius Rosenberg, apparently doesn’t signal to the antisemites that the Jewish contemporaries involved in support of Frank were acting on more than simple blood loyalty but actually believed in his innocence, much less that they perhaps had reason to.

I think an important factor contributing to the virtual consensus against Frank is that his modern-day defenders have very little by way of online exposure. Unsurprisingly, the exact opposite is true for those on the other side of the aisle who have created a number of websites that seem impartial enough until you come across the editorials with titles like “Jewish Men Dying in Jail for Ravaging Young Girls: Epstein v. Frank” and others written by Kevin Alfred Strom, who I'd imagine is especially drawn to the case out of his famous love for defenseless children. The purpose of this post is simply to make the Defense’s arguments more accessible, to illustrate the weaknesses of the Prosecution’s, and hopefully in the end, if I may be so naive, to contribute something productive to the discourse here.

The Obvious Perpetrator

I’ll assume the most basic facts are already known; the point of this post isn’t to recapitulate everything but simply to lay out the evidence for Frank’s innocence. For information about the case beyond the Wikipedia summary, the most definitive account is to be found in Steve Oney’s And The Dead Shall Rise—truly a masterpiece of research and prose that makes for excellent reading by itself—but I’ll also be drawing on Leonard Dinnerstein’s The Leo Frank Case (1987 ed.). Both are freely available online and rather than filling up the footnotes with superfluous citations, any quotes I draw from them can instead be easily searched in the texts.

Owing to the aforementioned facts, Jim Conley, a janitor at the National Pencil Factory, was the only person to ever be concretely (and confessedly) connected to the crime. All the evidence adduced against NPF’s superintendent served merely to corroborate the story his employee would come to tell. This being so, any reasonable assessment of the crime must start by assessing the plausibility of this story which, if substantially incorrect or improbable, would obviously tend to confirm the Defense’s position that it was Conley alone who murdered Mary Phagan.

Despite all the commiseration the anti-Frank crowd has for this man, just how lawless and indeed violent he was is not in dispute. Oney describes Conley’s criminal history as follows:

He had been arrested so many times for drunk and disorderly conduct that he'd adopted the alias of Willie Conley in the hope that he could stay one step ahead of the law. Most of his crimes had resulted in mere fines, but on several occasions, the offenses (among them a rock-throwing incident and an armed robbery attempt) had been more serious, and he had served two sentences on the chain gang. Three months before the Phagan killing, Jim had fired a shot at Lorena Jones [his wife] … Though Jim's aim proved faulty, he did graze another Negro woman standing nearby. The incident earned him a stay in jail.

Even after the lynching of the man he’d helped convict—at a time when you’d expect him to lay low for a while—Conley immediately returned to his usual, despicable ways:

[O]n November 1, 1915, Jim Conley was arrested along with ten other men and women in Atlanta's Vine City neighborhood at what the Georgian termed a “disorderly house.” The next morning, he was arraigned in police court. However, there, as the Journal dryly reported, “instead of drawing a fine, Jim drew a bride.” Throughout the remaining weeks of 1915, the first months of 1916 and, in fact, much of the next three years, Jim Conley would remain almost constantly in the news. Only now, the stories would chart a rapid spiral downward. On November 7, six days after his wedding, the new husband was picked up, in the Journal’s phrase, for “bride beating.” Several weeks later, he was arrested for the same offense. On February 13, 1916, the Constitution allowed that “Conley is ‘in again’ for wife beating.” Hard upon this spree, the man whose testimony had doomed Leo Frank was charged with public drunkenness, then vagrancy. By 1918, Conley, in one writer's estimation, had “spent more time in jail than out of it” since Mary Phagan's murder. And the worst was still to come. At 12:30 A.M. on January 13, 1919, during an attempted break-in at a West Side Atlanta drugstore, the Negro was shot in the chest by the proprietor, who had been lying in wait following a burglary several nights before. After a lengthy stay at Grady Hospital, Conley stood trial in superior court, where investigating officers testified that he had not only been in possession of tools useful in breaking and entering when apprehended but that he was suspected in 31 prior incidents. The jury quickly voted to convict, and Judge John Humphries pronounced a sentence of 20 years, whereupon Conley, far from looking stricken, burst into laughter. Cracked a court attache: “He figures the governor will pardon him out—the son of a gun.” [mine]

Conley would be detained only incidentally, four days after Mary’s corpse turned up in the NPF basement. A worker would report him scrubbing mysterious red stains out of his shirt on company property. It’s possible the stains were indeed rust as he maintained, and the police pursued the lead no further, but no laboratory test was apparently ever conducted.3 As trial witnesses would later testify, Conley had exhibited strange behavior in the days before his arrest.4 Before he was even detained, a worker’s wife who’d stopped by the factory on the day of the murder reported seeing an unknown black man loitering in the lobby either around 12:00 or 1:00.5 When Conley was eventually brought in for a lineup, an investigator would testify he “was chewing his lips and twirling a cigarette in his fingers. He didn't seem to know how to hold on to it. He could not keep his feet still.”

And yet after being jailed on May 1, the police showed him remarkably little interest; his presumed illiteracy at least precluded him from having written the notes. It was only on May 18 that Conley would give the first account of his whereabouts on Saturday, April 26. He described what was for him a typical weekend day: arising at 9–9:30 to drink and gamble on the town.

I think the benefit of hindsight is a major reason the crime looks so different to modern audiences than it did to the contemporary investigators and general public of Atlanta. People were gripped by a sensational crime—the body of the girl had been brutalized and strangulated, showing clear signs of a struggle—but obviously could not assess the totality of evidence yet. They were instead left speculating as the new leads and suspects slowly came in, putting pressure on the police to finally crack the case. This pressure was particularly heavy on Hugh Dorsey, Fulton County’s Solicitor General who took over the investigation already on May 5 after a series of widely-publicized prosecutorial losses.6

The police wouldn’t begin to suspect Conley of having been involved until almost a month after the crime was committed. And by then they, as well as much of the public, had become convinced of Frank’s guilt, though for reasons even less substantial than what would be presented at the trial. Chief among them was his nervousness when detectives arrived at his house early in the morning after telephoning about an unnamed “tragedy” at the factory he oversaw. After being informed Mary Phagan had been found killed and immediately taken to the mortuary to see her body, Frank seemed intent on distancing himself from the crime, claiming to have not even known the girl’s name and apparently repeatedly attempting to deflect suspicion onto Newt Lee, the black night watchman who’d discovered the corpse and called the police.7

In my mind much of this is understandable, especially since Frank was already known to be pretty neurotic. Fellow worker NV Darley, who would accompany Frank and the detectives back at NPF, recalled him trembling “just as much” after witnessing a gruesome car crash before work one day. As Frank would attempt to explain his conduct at the trial:

Gentlemen, I was nervous. I was completely unstrung. Imagine yourself called from sound slumber in the early hours of the morning, whisked through the chill morning air without breakfast, to go into that undertaking establishment and have the light suddenly flashed on a scene like that. To see that little girl on the dawn of womanhood so cruelly murdered—it was a scene that would have melted stone. Is it any wonder I was nervous?

But Newt Lee himself would lend the police further suspicions with descriptions of Frank’s conduct on the day of the murder. He described his boss uneasily sending him away from the factory at 4 PM. (As Frank explained at the inquest, he’d asked Lee to come early in case he wanted to catch the ball game but the cold weather had canceled his plans.) When Lee returned at the usual 6:00 to see Frank out, he described him as being unnerved by the presence of James Gantt who’d showed up to collect a pair of shoes. (Gantt had been recently fired by Frank, and Lee would testify it seemed Frank was afraid he’d come to “do him dirt.”) Later that night, Frank called Lee to make sure things were all right, something he’d apparently never done before, albeit Lee was a recent hire and Frank said he’d checked in on his predecessor fairly often.

Perhaps some of Frank’s actions genuinely were unusual, but the fairly reasonable explanations for them also weren’t immediately known to investigators and they only contributed to a mounting case against him. Additionally, a number of damning leads turned up against Frank early on, despite being dropped before the trial after proving to be false. They included an anonymous letter alleging Frank “had put his arm around her, and asked Mary if she wanted to take a joy ride of Heaven,” suggesting sexual interest as a motive, and the testimony of Nina Formby that Frank had called her asking for a place to store Mary’s body. This latter claim, which would contradict Conley’s story anyway, was initially regarded by police as “one of the most important bits of evidence they hold”—Formby and her maid would later say it was the product of police coercion.8

The police’s original working theory was, absurdly, that the crime was the product of an alliance between Frank and his black accomplice, Newt Lee. Notwithstanding the fact Lee was the one who discovered the body, the police had also regarded his behavior as suspicious and the murder notes were clearly written in black vernacular. So confident in fact were the detectives in this obviously false theory that at one point they announced to the press: “We have sufficient evidence to convict the murderers of Mary Phagan. The mystery is cleared.” But with such little evidence in reality and such popular indignation, it was certainly an atmosphere for wildly unjustified theories to take root. After establishing the involvement of Conley, the police would maintain their basic framework, simply swapping him and Lee.

On May 24, Conley would give his second affidavit, a first attempt at providing the police with a personally exculpatory narrative:

On the job, Friday, April 25, Frank called him to his office to write one of the notes at his dictation before rewarding him with a cigarette and $2.50. This is the first appearance of a line that would become a staple of Conley’s testimony, albeit in a different order: “Why should I hang? I have wealthy people in Brooklyn.” Interestingly, he stresses his ignorance as to specific details like Lucille Frank’s weight or Leo’s relationship to Brooklyn—things he could well have picked up over the months but which he implied were impossible to have known without his story being true. As Hugh Dorsey would argue in his closing remarks at the trial: “His people lived in Brooklyn, and that's one thing sure and certain, and old Jim never would have known it except Leo M. Frank had told him.”

The Murder Notes

The so-called murder notes themselves played a surprisingly small role at the trial, but would become the center of Frank’s defense during the appeals process. In fact, among other things, the two notes formed the most important piece of evidence that eventually convinced Jim Conley’s own trial lawyer, William Smith, to conclude his client had deceived him and forcefully rally to Frank’s cause. Despite defending Conley pro bono out of a lifelong belief in racial equality, Smith’s sudden volte-face would singlehandedly ruin his legal career in Atlanta, bombarding him and his family with pervasive and—in view of the violence directed at others—quite serious death threats. Frank’s enemies of course recognized how significant the event was, and yet, despite their insinuations, there can be no doubt it was genuine. Upon visiting his son decades later, Oney discovered a signed statement Smith left on his deathbed: “In articles of death, I believe in the innocence and good character of Leo M. Frank.”

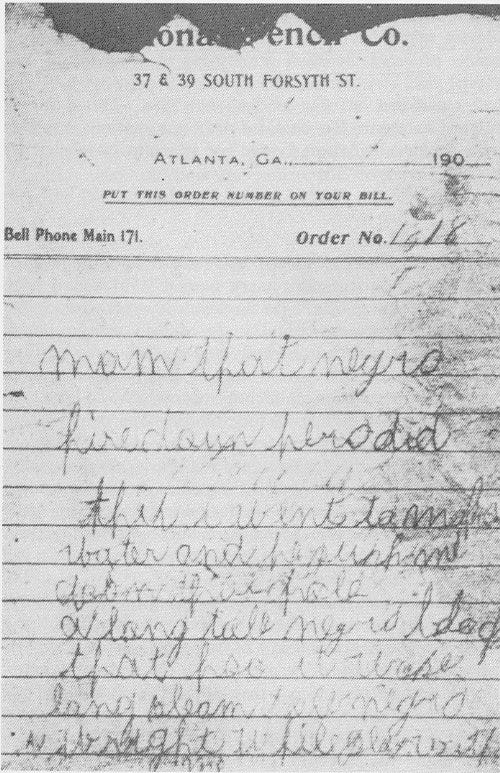

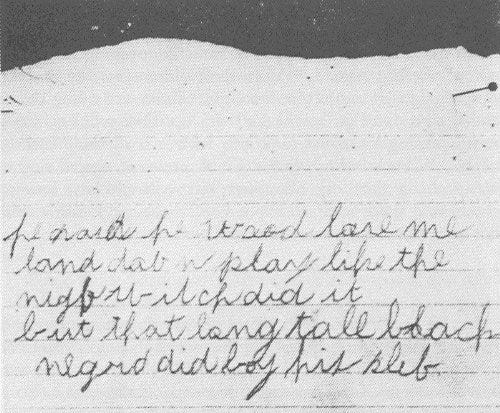

The murder notes are as follows:

mam that negro hire down here did this i went to make water and he push me down that hole a long tall negro black that hoo it wase long sleam tall negro i wright while play with me

he said he wood love me land down play like the night witch did it but that long tall black negro did boy his slef

The idea behind them should be immediately apparent: written in the aftermath of the murder, the author actually intended to fool whoever would find the body with a message purportedly written by Mary herself and pointing a finger at a perpetrator. Accordingly, Mary had gone to “make water” (old black slang for urinate) when a tall, slim black man pushed her down a hole (perhaps one of the scuttle holes linking the lobby to the basement below) before apparently sexually assaulting her (“play with me,” “wood love me”). Although it was at first unclear to me who “mam” was referring to, Conley’s rewording in his second affidavit (“dear mother”) suggests the notes are actually addressed to Mary’s “mom.”

There was some debate among the Defense as to whom the notes were intending to implicate, largely because the wording is so poor and confusing; some suggested William Nolle, the black plant boiler operator. In any event when the illiterate Newt Lee heard the call officers first read the notes, he remarked upon hearing of “the night witch” that the author was trying to “put it off on” him, and Conley seems to suggest as much later on. Either way, the emphasis on the perpetrator’s slimness makes it clear he was depicting a stature dissimilar to Conley’s own short, stocky figure.

While the specifics of his story would change drastically over time, Conley would always maintain that while the notes were by his hand, he’d simply written them at Frank’s dictation. But how anyone other than a monomaniac could take his word for this is beyond me. It’s simply too obvious the Cornell-educated superintendent would realize the notes would fail in their immediate purpose of implicating another target: disregarding the logistics of the girl scribbling them as she was being murdered, they weren’t in her handwriting or diction. That being so, their real purpose was never fully explained by the Prosecution. If in devising them, Frank was instead perhaps trying to pass blame onto Conley, then why was he so intent on blaming Newt Lee before Conley was detained by sheer accident? And, at least in keeping with the narrative of Affidavit II, why would Frank even go out of his way to involve another person in such a crime simply to utilize his handwriting?

Yet it was Conley’s insistence that the notes were written at Frank’s own dictation, verbatim, that ultimately dissuaded his attorney. Smith eventually drafted a 100-page comparative study of the phraseology and verbiage of the notes with Conley’s own language as used elsewhere, notably during the cross-examinations at the trial, finding them fully consistent: this was exactly how Conley talked, and was unlikely to be a simple imitation quickly cooked up by Frank.9 Smith naturally had no luck relating these findings to his former colleagues.

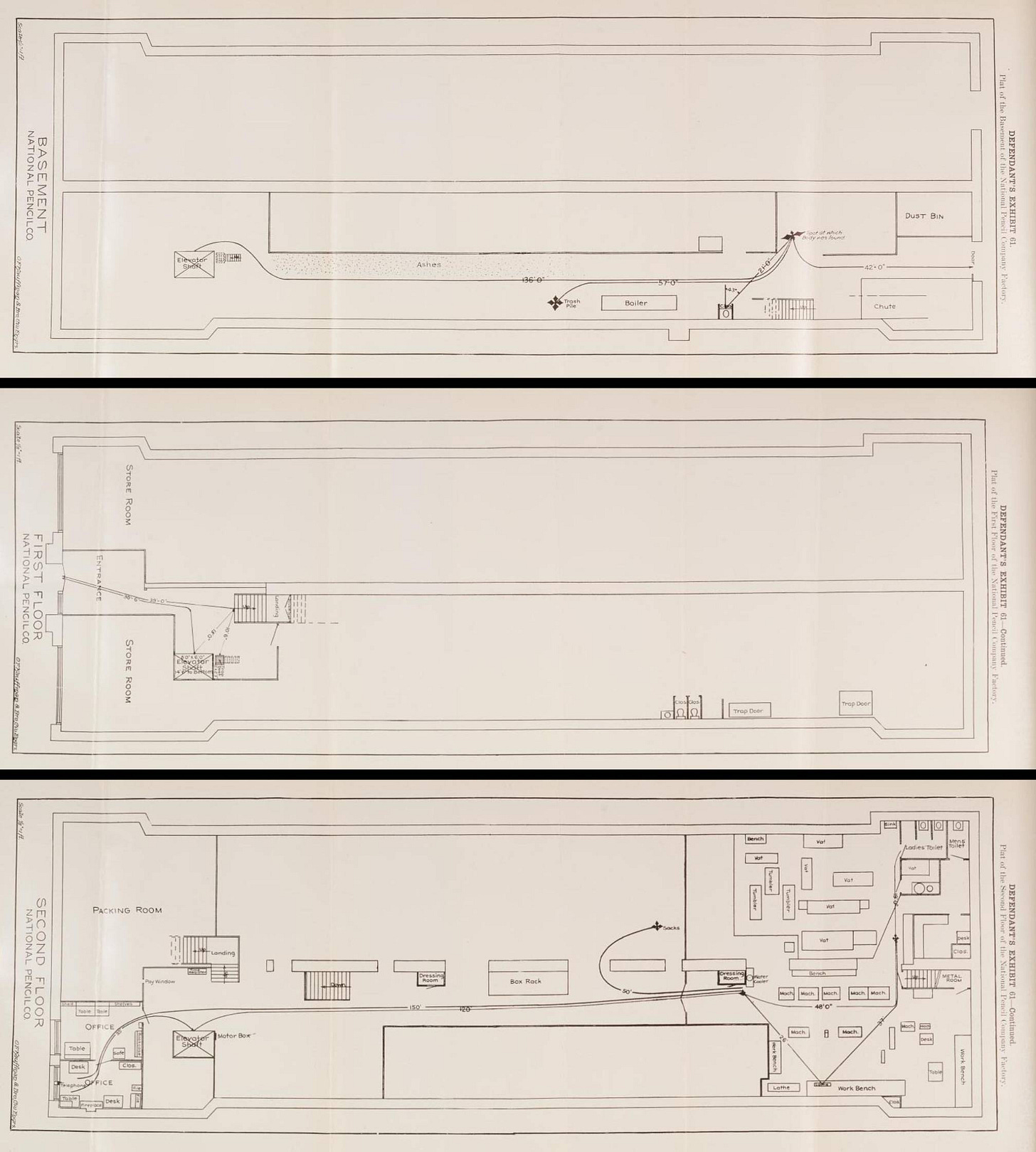

And there are still further features of the murder notes that called into question Conley’s narrative. While the notes were allegedly retrieved from Frank’s office, the Defense would discover they were years outdated, visibly bearing a 190_ dating, an old order number, and even the carbon imprint of the previous superintendent’s signature. While there would be debate at the trial over whether superintendent Becker’s order pads had been stored in the basement (per the testimony of Herbert Schiff) or in the closet near Frank’s office (per Chambers, Gantt, and Otis), they clearly would not have been in use by Frank himself. On the other hand, Dobbs and Anderson, members of the first police dispatch to arrive at NPF, would recall seeing “paper and pencils down there” in the basement, scattered among the filth.

A Changing Script

“But what a statement! So full of contradictions, so evidently made for self-protection and wherein was so easily apparent the guiding hand of detectives.” —Luther Rosser, Frank’s attorney

The police, I suppose to their credit, rejected Affidavit II outright, mostly because it suggested premeditation for what was quite evidently a crime of passion. In an incredibly revealing testimony at the trial, one of the investigators would recall their interrogation tactics:

We tried to impress him with the fact that Frank would not have written those notes on Friday, that that was not a reasonable story. That it showed premeditation and that would not do. We pointed out to him why the first statement would not fit. We told him we wanted another statement. … Chief Langford and I grilled him for five or six hours again, endeavoring to make clear several points which were far fetched in his statement. We pointed out to him that his statement would not do and would not fit, and he then made the statement of May 28th

The following affidavits, as well as other testimony from the trial, can be found here.

On May 28, Conley updates his story: after arising 9–9:30 on April 26 and going about his day like normal, he randomly meets Leo Frank on the street corner. Frank brings Conley back to NPF to sit on a box sequestered near the lobby stairs where he recalls seeing descend workers such as Mrs. Mattie, Darley, Holloway, a “peg-legged black man,” and a woman in a green dress whom he noticed counting her pay at the bottom of the stairs. Frank then whistles to call Conley up into his office before hiding him in a wardrobe as Emma Clark and Corinthia Hall unexpectedly appear. Then the usual: Frank dictates the notes, rewards Conley, asks “Why should I hang, I have wealthy people in Brooklyn?” Then Conley seemingly gets carried away:

I didn’t have any idea in the world what he was talking about, and he was winking and rubbing his hands together and touching me on the shank with his foot and took a deep breath, he said “Why should I hang?” and shook his head and rubbed his hands together … he stuck one finger in his mouth and said “S-s-s-h, that’s all right,” and then Mr. Frank told me he was going to take that note I had written and send it off in a letter to his people when he wrote, and recommend me to them

After being asked, he informs Frank he had no idea who the night watchman was or what he did, before reiterating the details about the reward money and the “Why should I hang?” line, as if he’d forgotten he’d already used them. Amazingly, the investigators respond positively to this version:

“The negro's affidavit,” reported the Journal, “is regarded by the detectives as the most important link in their chain of evidence against the factory official.” Echoed the Georgian: “Chief Lanford and Scott announced Thursday that they considered the negro's final affidavit proof conclusive of the suspected superintendent's guilt and were thereby ready to place the case on trial.”

Harry Scott insisted that it “had practically cleared the mystery and was the most important bit of evidence in the hands of the state.” At headquarters, the reviews were just as glowing. “The negro Conley is regarded by detectives as their most material witness,” reported the Constitution. “He is the missing link, they think, which connects the chain of circumstantial evidence which they have gathered.”

And yet by the very next day, Conley had revised his story yet again. As Affidavit IV would have it, after returning to the factory and being cued to come upstairs, Frank informed Conley “he had picked up a girl back there and had let her fall”—Conley finally admits to having known about the murder. He then describes the process of depositing her body in the basement, first by bringing her from near the men’s toilet by the metal room to the lobby elevator, right by the building’s entrance. For some reason, Conley asks for something to “pick her up with,” fetching a “big wide piece of cloth,” and then has Frank help carry her body after finding it too heavy. In the basement, Conley transports the girl on his shoulder before dropping her on a lump of sawdust, throwing her personal effects on a trash pile nearby. They return to Frank’s office, and repeat the aforementioned business. Frank then hands Conley $200 for his efforts, yet handwritten at the bottom of the original affidavit is the anticipated explanation for why Conley didn’t actually possess that piece of evidence: Frank had taken it back, promising it “Monday if I live and nothing happens.”

At the trial, Conley would revise yet again with still further information, revealing, for example, that he’d long been tasked with staying watch at the factory for Frank’s Saturday afternoon sexual escapades; the meeting on the street corner was in fact not chance, but planned the day prior. In total Conley would offer no fewer than five meaningfully different accounts of his activities on or around 4/26. The totality of all these confessed lies and distortions obviously means the value of his testimony is and should have been treated as effectively worthless. But even if we’re being as charitable as possible, it’s quite difficult to see this as consistent with anything other than the behavior of someone clumsily yet deliberately fabricating a narrative for self-protection. Assume Conley was in fact Frank’s accomplice. Perhaps Affidavit I can be excused as a way to simply avoid involvement. In Affidavit III, Conley rationalizes the fabricated Affidavit II as an attempt to avoid being suspected of the murder:

I made this statement in regard to Friday in order that I might not be accused of knowing anything of this murder, for I thought that if I put myself there on Saturday, they might accuse me of having a hand in it, and I now make my second and last statement regarding the matter freely and voluntarily, after thinking over the situation, and I have made up my mind to tell the whole truth, and I make it freely and voluntarily, without the promise of any reward or from force or fear of punishment in any way

This is despite the fact Frank’s “Why should I hang?” comment could not have been clearer. In Affidavit IV, where he admits to having partaken in the disposal of the body, Conley adds an explanation for his incredible reticence: “The reason I have not told this before is I thought Mr. Frank would get out and help me out, but it seems that he is not going to get out and I have decided to tell the whole truth about the matter.” But again, Conley himself had already named Frank as the murderer by implication since Affidavit II. The only honest way to square away these contradictions is, of course, to recognize Conley was a murderer simply covering his tracks before an exceptionally motivated police force.

The Trial Narrative

Yet no matter how much the police worked with him, Conley could never create a truly convincing counter-narrative, invulnerable to meaningful attacks by the Defense. The following is the state’s final theory of the case in the form of Conley’s testimony, annotated.

Conley often came on Saturdays to watch the NPF’s front door “while he was upstairs talking to young ladies,” offering the example of Thanksgiving, 1912. But everyone10 who worked at the factory on Saturdays denied ever seeing these unknown women or finding the door locked. (Why Frank would need someone else to lock the door in the first place goes unexplained.) Day watchman Holloway and assistant superintendent Schiff claimed servicemen and even Frank’s wife would often drop by unannounced; Schiff even recalled ordering Conley to clean a room on Thanksgiving and seeing him out by 10:30, something corroborated by Conley’s coworker, Frank Payne. Leo Frank’s office, like the metal room, also had windows without curtains; when William Smith returned to the factory to reassess the crime, he counted “43 windows in the buildings on the opposite side of Forsyth Street that offered clear sight lines into the space.”

When Conley arrives after being told to come in the day before, Frank realizes it’s too early and they agree to meet up on a street corner later. He then shows Conley how to lock the front door as well as specific cues like stomping (lock the door) and whistling (unlock the door and come up). Thus the street corner meeting and Frank’s whistling are given new meanings. When asked by the Defense why Frank would explain to him cues they’d already used in the past, Conley claimed he simply didn’t know. Regardless, the idea is that Frank had planned to spend this Saturday with Mary Phagan.

The aforementioned workers enter and exit the factory, with Conley adding in foreman Lemmie Quinn before “Miss Mary Perkins,” that is, Phagan, finally enters and goes upstairs. But Quinn long maintained he’d arrived at 12:20—minutes after the estimates either side offered for when Mary would’ve arrived—and observed Frank working at his desk. Indeed, Frank’s extensive workload was confirmed at the trial based on the financial sheets he’d completed, estimated by relevant experts to have required 172–191 minutes. Additionally, the stenographer Frank was working with, Hattie Hall, claimed he hadn’t even started on the financials before she’d left with office boy Alonzo Mann around 12:00. Schiff agreed Frank ordinarily did such work in the afternoon, suggesting a significant portion of Frank’s day was occupied with studious work after committing a grisly murder. Hall also testified that Frank had begged her to come in Saturday, telling her “he had work that would take him until 6 o'clock” and asking her “to stay all afternoon and help him” before phoning another worker to drop by after lunch when she’d declined.

Leo Frank’s own account was fairly straightforward: he’d been busy in his office all morning with Hall and Mann. Sometime after they leave at noon, Mary Phagan arrives to collect the weekly pay she’d missed on Friday, having had little work that week because of a delay in a shipment of metal. At the inquest Frank estimated this was “between 12:05 and 12:10” while at the trial he held it was more like 12:10–12:15; in any event, admitting early on to having been the last known person to see Mary alive seems far riskier than claiming she’d never entered his office. Before leaving, she asks Frank if the metal had come in, to which he’d told her no. Despite having consistently reported this response, investigator Harry Scott claimed it was actually “I don’t know” at the trial, arguing he’d misremembered before. The Prosecution’s theory, then, is all but spelled out by Conley’s testimony: footsteps are heard going from Frank’s office to the metal room, before screams. Smith would later claim such screams were impossible to hear from Conley’s position on the first floor.

Worker Monteen Stover enters and goes upstairs before leaving. Stover had testified to coming in 12:05–12:10 to collect her pay, but not seeing Frank in his office. This does contradict Frank’s recollection of having been in his office through the relevant period, with the Defense later arguing either an opened safe door had obscured his position behind the desk in the inner room or that he’d simply forgotten stepping out for a moment; for the Prosecution, this means Mary must’ve entered prior to 12:05 and was being actively murdered in the other room. But this arrangement also implies Frank had forgotten to signal to Conley to lock the door. As Governor Slaton would remark in his commutation order, it isn’t “easy to comprehend the use of the signals which totally failed their purpose.”

Conley falls asleep but is awoken to stomping and whistling, and he meets a shivering Leo Frank at the top of the stairs, still holding the very cord he’d strangled the girl with; he explains he wanted to “be with the girl” but her rejection led to a violent altercation and ultimately her death. But it strains credulity that the mild-mannered Leo Frank at 5’6”, 120 lb could pull off such a feat with his bare hands despite showing no scratches or wounds when stripping before police just a day or so later. Additionally, as Smith would emphasize, the body of Mary Phagan, with dirt in the eyes and mouth and which was so covered in soot that the officers couldn’t initially tell her race, displayed clear signs of a struggle in the basement.

Before Conley readily obliges to carry the body to the basement, he “noticed the clock … was four minutes to one,” 12:56. After struggling, he requires Frank’s assistance carrying the legs, even though the girl weighed a mere 105–110 lb. In a statement to the Atlanta Journal about this moment, Conley had noted “when I lifted her body to push the crocus bagging under it11 I took hold of her forearm and it was cold,” despite her just having been killed. It was statements like these, Smith would recall, that had convinced Dorsey to move Conley to the station house where access would be reserved “to only such officials as were approved by me,” Hugh Dorsey. The Defense of course realized the dishonesty of such an arrangement and appealed to the judge well before the trial, but because of a completely dishonest yet fairly convoluted legal maneuver12 Conley was allowed to remain at the disposal of the Prosecution, tucked away from the press, unlike any other material witnesses. It was the exclusive prep sessions conducted here for weeks that aimed, in Smith’s words, “to render Conley impervious to cross-examination.” Conley would also be provided with the daily newspapers covering the investigation, despite pretending he could barely read them at the trial.

The two descend to the basement where Conley puts the body over his shoulder and lays it where it would ultimately be found the next morning. This is despite the elevator being located right in front of the unlocked NPF entrance, and which according to Darley “was so creaky that if … it had been used to take Mary Phagan’s remains to the basement, the two workmen laboring upstairs at the time would have heard it,” though the Prosecution disputed this.

Further was the Defense’s infamous “shit in the shaft” argument made during the commutation hearings. Officers arriving at the basement on April 27 had described “a fresh mound of human excrement that looked like someone had dumped naturally” in the elevator shaft, and Conley indeed—for frankly whatever reason—admitted to having been responsible for it the morning of. Yet Frank, Darley, and the detectives had used the elevator when arriving at NPF. As Frank’s lawyers would argue: “in running the elevator down, the investigators smashed into the stool, and the smell of it revealed its existence. Now mark you, if they had brought the body down in the elevator on Saturday it would have smashed the excrement then.”

But of much more weight, in my opinion, is the famous, late-in-life testimony of Alonzo Mann: after heading out of the factory, the office boy had returned “a little after 12:00” to personally witness Jim Conley carrying Mary’s limp body, presumed unconscious, in his arms, alone and near a scuttle hole in the lobby. Detractors of course maintain the aged Mann was simply lying, but for what it’s worth the paper that first interviewed him “asked him to submit to both a lie detector test and a psychological stress evaluation examination … and investigator Jeffery S. Ball provided the newspaper with a formal statement saying Mann responded truthfully to every question he was asked.” As to why Mann didn’t volunteer this crucial testimony as a 14 year old at the trial, he claimed he was simply following the direction of his mother who told him “not to get involved.” Indeed, as the Atlanta Journal noted at the time, Mann “was frightened by his experience in court, and the stenographer had difficulty in hearing his answers.” It would’ve been dangerous to have volunteered it soon after the lynching, but in the 1980s with failing health it was allegedly haunting his conscience.

Conley throws all her belongings, including her umbrella and hat, in the basement. But the cloth and, notably, her purse and pay envelope were never recovered. After they return to Frank’s office, Conley is hidden in the wardrobe as Clark and Hall appear before writing the notes. Never even challenged by the Prosecution, however, is the testimony of Emma Clark and Corinthia Hall themselves that they’d actually appeared between 11:35 and 11:45.

Finally, in a perplexing revision of Affidavit IV, Conley avers that the real reason Frank withheld the $200 reward was that it was contingent upon his demand Conley incinerate the body in the basement furnace. Despite obeying Frank without hesitation in the removal of a corpse, Conley at first refuses—to which Frank rhetorically asks “Why should I hang?” and rubs his hands—but he eventually agrees to come back “this evening,” i.e., in 40 minutes or around 2:00, after Frank eats “dinner,” i.e., his lunch. Some have wondered why Frank would even have created the notes, whatever their rationale, if he planned on incinerating the body, but Conley’s testimony seems to conceive of them as a makeshift “plan B.” Indeed, the body—notes nearby—was not burned, with Conley claiming to have simply gotten drunk after leaving NPF “about 1:30” and forgotten to return to finish the job.

The Defense offered the perspective of a Dr. William Owens, who estimated after a recreation that all of Conley’s described acts would’ve realistically taken from 12:56–1:32, which seems reasonable enough to me. And yet according to all those in question, shortly after 1:00—there was debate over whether it was 1:00 or 1:10—Frank met with the two workers laboring on the factory’s fourth floor this whole time, as well as the aforementioned wife who spotted Conley downstairs. Frank was then sighted on the street at 1:10 according to three witnesses13 before being seen arriving home around 1:20 where he’d enjoyed lunch with his wife and her parents and then left around 2:00. Not only did the by all accounts neurotic man who’d just committed a heinous murder not appear shaken, the very act of leaving the body in the building with others to attend lunch, undisputed by the Prosecution, seems entirely out of place.

But the most puzzling thing of all is the following: to believe in Conley’s testimony on which Frank’s guilt hinged is to believe Leo Frank decided to simply leave the body of his victim in the basement upon heading out for the night, only for it to inevitably be discovered by his own night watchman with nothing but the “murder notes” as his ingenious coverup. There was evidently abundant time between 1:00 PM and its eventual discovery at 3:00 AM to more properly dispose of Mary’s body and things, or at least to move them off company property and to a location that wouldn’t directly implicate him. My own thought process is that this is all so absurd because it’s untrue.

By far the more reasonable explanation for Mary’s death was outlined in basic form by the Defense and confirmed by Mann: Conley was loitering in the NPF lobby that Saturday, saw Mary descend with her pay envelope and her purse, and like any drunken wastrel accosted her, knocking her out and finishing the job in the dingy basement where nobody would interrupt. Indeed, one critical piece of evidence left totally unaccounted for by the Prosecution was the presence of bloody fingerprints on the basement door and a pipe that had apparently been used as a crowbar. The prints, which “had remained in situ until the Tuesday following the killing when a private citizen had taken it upon himself to chisel them off,” were never matched to Jim Conley by the police. Upon learning this, William Smith acquired them and attempted to finish the job himself. Still on good terms with Conley after the trial, he tried to capture prints of his hands nominally for a pair of gloves only to find the man, inexplicably, all too reluctant.

A Paradoxical Conviction

An obvious question follows: if the case were so clear-cut,14 then why was Frank convicted, and why did the public rally against him? After all, this was the Deep South just 50 years out from the Civil War. Indeed one of the reasons the Frank case is so historically significant is that, for apparently the first time, we find a white man sentenced on the testimony of a black man.

Of course on the Internet this is taken as much more than an interesting fact worthy of explanation, but proof conclusive of Frank’s guilt. According to what I could glean from the incredibly pervasive meme-history, Frank apparently “went to the KKK” blaming a poor, innocent black man only for the Klan itself to ultimately “side with the black guy”—what other proof could you need? Every time Leo Frank reenters the limelight, this is by far the single most common characterization you see of the case.15 (No matter the fact the KKK didn’t even exist at the time, having disbanded in 1869 and not reemerging until after Frank’s lynching.) At some point the absurdity becomes almost too much to bear. After all it’s not every day you see self-styled white nationalists shedding tears over the wrongly-accused black man. But here as with the “Jewish slave ships”—or with their dastardly ownership of record labels and football teams or basically anything laid at the hooves of the Jews by the Yakub people—such types will without hesitation join in the chant: “the Jews are the real racists!”

At any rate the case against Frank was indeed circumstantial and rested entirely on Conley’s fallacious testimony. Some scattered evidence was proffered to corroborate certain points—conversely, Conley’s narrative would change to reflect what was thought to be evidence. One element was Frank’s unusual behavior the day after and, as the Prosecution argued, the day of the murder. Then there was the discrepancy in Frank’s account offered by Monteen Stover. Another key piece of evidence was the Monday discovery of a red splotch on the metal room floor and female hair on one of the lathes, leading to the metal room theory of the murder site. While neither was noticed there the Friday before, they also hadn’t been spotted by the dozens of investigators that Sunday. Dr. Claude Smith, who examined the red spot, reported, among other elements, “four or five corpuscles of blood of indeterminate origin.” The hair, on the other hand, was determined to have been of a different composition than Mary’s by Dr. Henry Harris, a fact never revealed by Dorsey to jurors, though after the trial he’d argue the soap with which the body’s hair was washed at the morgue could’ve been responsible for the discrepancy.

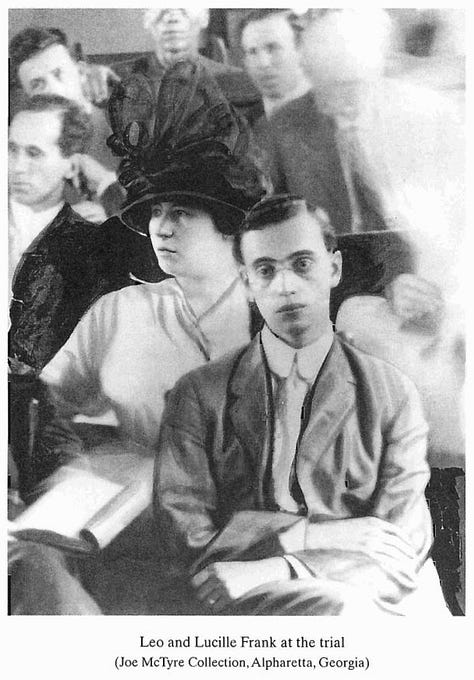

But there were stronger factors at play that affected the jurors’ judgment more than individual pieces of evidence. While it was debated vigorously in the appeals process exactly what role the incredibly hostile atmosphere played, it undoubtedly had some impact. Outside the courthouse stood a perennial crowd peering in; anti-Frank outbursts occasionally rang out among spectators inside. Upon the reading of the verdict, a parade was launched in the streets. Oney quotes the Constitution:

While mounted men rode like Cossacks through the human swarm, three muscular men slung Mr. Dorsey on their shoulders and passed him over the heads of the crowd across the street. With hat raised and tears coursing down his cheeks, the victor in Georgia's most noted criminal battle was tumbled over a shrieking throng that wildly proclaimed its admiration. Few will live to see another such demonstration.

While the notorious “hang the Jew!” line is probably apocryphal,16 there’s no doubt this mob was at times violently agitated against Frank. Judge Roan—who, like Smith, had serious doubts about Frank’s guilt—ordered him not be present for the verdict, apparently due to serious fears of a riot in the event of a “not guilty.”17 These concerns only became more apparent after the trial, when the Defense’s investigators were assaulted and chased out of Marietta. Upon deciding to commute Frank’s sentence to life imprisonment after a study of the evidence, three separate mobs attempted storming Governor Slaton’s residency leading to a declaration of martial law. This isn’t even to mention the kidnapping of Frank from the state prison and his subsequent lynching by highly prominent members of Georgian society. Even if the jurors didn’t personally fear for their lives, I don’t think there’s much doubt they were nudged against Frank by all this to some extent, even if only from, say, the vibes.

There were also serious inadequacies with the trial’s Defense, which, for example, neglected the murder notes almost completely. They also made it part of their strategy to discredit medical findings indicating sexual assault, which I think was unnecessary; their theory that the murder was a result of theft didn’t rule out the sexual violence Conley himself seemed to imply in the notes. But most importantly, a key part of the Defense’s strategy was to summon witnesses testifying to the good character and morals of Leo Frank. In doing so, they broached a topic that otherwise would’ve been declared immaterial, allowing the Prosecution to call their own character witnesses who would testify to his alleged sexual improprieties shortly before the verdict was decided. Most were former factory girls who tersely described Frank’s character as “bad.” Some mentioned a habit of peeking into the dressing rooms or being too handsy with the girls. Nothing even approaching rape and murder was ever alleged,18 but the display only bolstered the Prosecution’s theorized motive and confirmed long-held suspicions that Frank was abusing his position to exploit teenage laborers.

The “racist southerners” narrative people so often use to “prove” Frank’s guilt isn’t just the kind of immature meta-take that excuses one from actually learning the facts of the case, it’s also a massively reductionist view of southern society that eliminates all social factors at play save the race issue. But the Frank case can never be fully understood without an acknowledgement of the economic context of Atlanta, a rapidly industrializing society whose population quadrupled between 1880 and 1910. Of all the accompanying unpleasant changes—inadequate public services, crime, vice, the erosion of social norms—by far the most personal was the issue of child labor. Georgia had the lowest limit in the country, while lacking “even the semblance of factory inspection, and employers openly violated existing laws prohibiting employment of minors under ten.” Atlantan parents like those of Mary Phagan deeply resented being forced to send their young daughters away to labor often for Yankee-owned firms; fears of sexual exploitation were always implicit. One could see just how much the mangled corpse of one such girl found in her place of work would ignite these concerns. As the Phagans’ family minister himself would write years later, a black man like Conley “would be poor atonement for the life of this innocent little girl,” but “a Yankee Jew … here would be a victim worthy to pay for the crime.”19

The deliberations of the jurors is one thing, but I think these tensions between cracker and industrialist, southerner and Yankee go a long way to explain the decidedly less sober perspectives of the masses. Jewish collective memory—which like many complimentary ethnic histories tends to work its way into the mainstream—often presents the event simplistically as a spontaneous act of antisemitism. Yet it would be a mistake to conflate the antisemitism of the South with that of Russia, concurrently hosting a blood libel trial against Mr. Beilis, as so many of the day’s Eastern European Jewish immigrants were wont to do. This obviously isn’t to suggest, as some might, that antisemitism played no part in Frank’s persecution. Indeed antisemitism has always been a feature of anti-Frank agitprop; many contemporary Atlantans even interpreted Frank’s alleged deeds along the lines of the same rumors we hear today about the Talmud and Jewish law.20 But antisemitism was more like a tertiary layer that meshed with much deeper class conscious or anti-northern sentiments. The post-trial media campaign waged by urban Jewish businessmen to overturn Frank’s conviction, for instance, was easily perceived as another northern attack on southern sovereignty.

Toward the close of his book, Oney asks, “was there some element of truth to the charges, one that while far from making Frank a murderer haunted his conscience and compromised his ability to mount the sort of righteous defense that would have carried the day?” That Frank was guilty of the indecent behavior attributed to him should not be ruled out, and the testimony either way had a powerful effect on both the jurors21 and public. Nevertheless the question is not whether Frank was without sins, or even a decent man, but whether he murdered Mary Phagan. And at the end of the day, all the circumstantial evidence one could assemble against him simply pales in comparison to the case against Jim Conley, the actual murderer of Mary Phagan, and the one who actually escaped justice for his crime.

Though it also seems the author was mixing together Newt Lee (the night watchman who discovered Mary’s corpse) and Conley (the janitor).

I assume most just infer from the Irish surname, but this was inherited from her biological father who passed away before she was born; her mother remarried to John Coleman.

Oney, 426. Conley also lied about the shirt being the only one he owned: Oney, 129.

Oney, 293, 295. Showing up for work unusually well-dressed and dropping out when the crime was brought up in conversation.

The former was the time initially reported and later insisted upon by her brother; the latter was Mrs. White's recollection at the trial.

The act of a prosecutor taking the reigns from the police was "unheard of in Georgia" (Oney 2003, 93). It was widely believed the Phagan case would represent a last chance for his career (95; Dinnerstein 1987, 57) and he eventually rode the fruits of its success to the GA governorship.

The police would even suspect him of falsifying Lee’s time slip and planting a bloodied shirt, though these were speculative and never proven.

Dinnerstein, 28, 85.

Some excerpts of the study are quoted by Oney but I don’t believe the full thing has been digitized.

The drayman, the handyman, office boy Alonzo Mann, former office boy Philip Chambers, Schiff, Holloway

As Slaton notes, Conley was never consistent about the type of material he used to carry the body with.

Oney, 172–175.

Helen Kerns as well as Ethel Harris Miller and Maier Lefkoff

Barring, of course, much of the evidence above that was unavailable to the jury, being unknown to (or unrealized by) the Defense.

Alternatively, a member of the Owens School of Historiography might suggest the lynching was itself an inside job because after all, "as many know, the ADL had ties to the KKK."

Oney posits it came from CP Connolly's recollection in the articles he wrote for Collier's of a similar death threat received by Frank's lawyers. To me it sounds an awful lot like the "Mort au juif" cries reported during the Dreyfus affair, which was very much still hot in the Jewish consciousness.

Dinnerstein, 54–55.

On occasion, while cross-examining witnesses for the Defense, Dorsey would make reference to bizarre rumors, even attributing pederasty to Frank, but he never provided witnesses to substantiate them. It should also be noted that the Defense called their own factory girls to dispute certain accusations or attest to Frank’s good conduct.

More about these issues can be found in Nancy MacLean's "The Leo Frank Case Reconsidered," but the development of the South is a context mentioned in basically any thorough treatment of the Frank case.

Dinnerstein, 18; Oney, 598; Connolly, 14.

This was suspected by Luther Rosser, who would argue before the Georgia Supreme Court, “The jury may have thought they were writing ‘guilty of murder,’ but your honors, what they wrote in reality was ‘guilty of perversion.’”

Always bothered me with the simple minded “It must have been Leo because why would whiteliners push away an opportunity to hang a black guy!!!!???”

Antisemites never think deeper than surface level begging the question, it’s very disappointing. Although I dislike the ADL for their approaches to antisemitism it’s undeniable that Frank was not the culprit (at least to anyone who’s gone further than simple minded ignorance)

Great article and welcome back to (hopefully frequent) writing. This reminded me of two themes David Cole writes a lot about. One is how desperate even avowed white supremacists are to participate in the negrolatry that permeates American culture, and the other is how police investigators often reproduce the same mental habits as conspiracy theorists.

https://web.archive.org/web/20170616235121/http://takimag.com/article/how_your_bs_conspiracy_theories_help_the_state_david_cole/print