The following is part of a trilogy on the blood libel; see Part I.

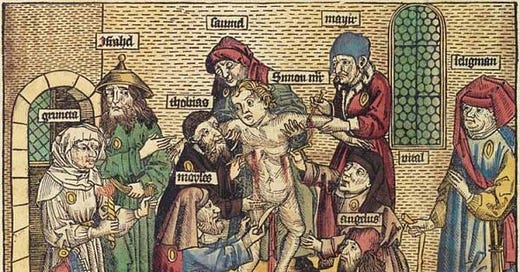

The immediate focus of Toaff’s book is the late medieval blood libel in the Italian city of Trent. In 1475 Trent hosted a recently formed community of a few dozen Jews arranged into three households headed by the patriarchs Samuel, Engel, and Tobias. At 5 PM on Maundy Thursday of that year’s Holy Week, March 23, the boy Simon disappeared from his parents’ sight. As March 23 also marked the second night of Passover, the anticipated rumors immediately began to spread. When Andreas Garbarius (alternatively Unferdorben or Lomferdorm) reported his son missing the following day, a search of the Jewish residences was conducted, turning up nothing.

But on Easter Sunday, March 26, per the trial records, the Jews reported to the podestà the discovery of the boy’s body. It had been found in the canal connected to the mikveh in Samuel’s cellar by a servant sent to gather water. All too predictably, the men were promptly arrested and sent to the Castello del Buonconsiglio for further questioning; officially this was because Simon’s body had begun to bleed in their presence, as if it were pointing out its murderers, a medieval superstition known as cruentation. Two witnesses would testify to having heard a crying child in Samuel’s home—one had understandably assumed this to be one of the many Jewish children—and in the days to come the Jewish prisoners would each make detailed confessions about the boy’s killing and the ritual usage of Christian blood. As befits any martyr worth his salt, the first bodily miracles were reported on March 31, and ultimately “[b]etween 31 March 1475 and 29 June 1476, no fewer than 29 miracles were attributed to Simon.”

Toaff’s description of these events is as follows, taken from the unofficial English translation but confirmed in the original:

On 23 March, eve of Passover of 1475, year of the [Catholic] jubilee, the mutilated body of Simonino, a two-year old child, son of the tanner Andrea Lomferdorm, was found in the waters of the ravine by-passing Samuele’s cellar.

Ignoring the obvious misdating, Toaff resorts to the passive voice to omit a quite relevant fact: that the Jews themselves were the ones who found and reported the body to the authorities. (I don’t necessarily accuse him of bad faith here, but this is only the first reminder that Pasque should be supplemented with a more standard historical account like Hsia’s Trent 1475.) It’s conceivable a criminal might report the corpus delicti in order to deflect suspicion, but this would probably not be the case if there were already rumors in the air accusing him of the crime, certainly not if the body bore direct signs of said crime—that is, ritual abuse—as the autopsists would soon maintain, namely in the form of heavy scratches including to the foreskin.

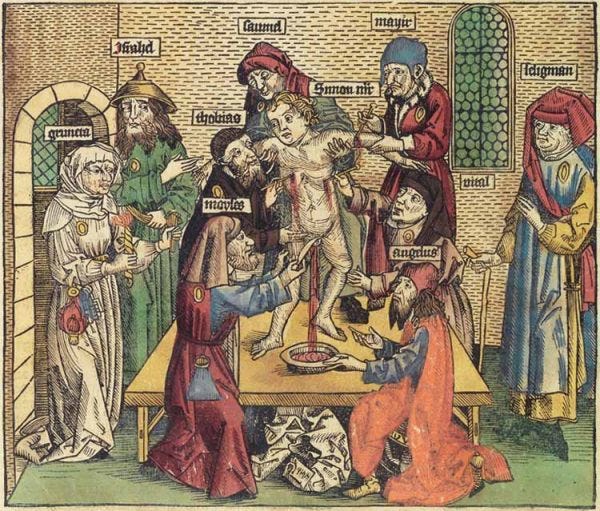

It should be clarified that Toaff does indeed believe Trent (1475) was one of a number of instances of Jewish ritual murder, notwithstanding his later protests. Despite originally announcing outright that “some ritual killings could have happened” he would soon insist this “statement was an ironical academic provocation, designed to begin the process of breaking the taboo.” He would eventually withdraw his book and issue a revised edition with an even more emphatic Afterword: “I shall clarify that I have no doubts that the so-called ‘ritual homicides or infanticides’ pertain to the realm of myth; they were not rites practised by the Jewish communities living and working in the German-speaking lands or in the North of Italy.” That this is a revision, not a clarification, is obvious in a reading of the first edition—though he does allow that once the rumor got going “the Jews were accused of every child murder, much more often wrongly than rightly”—which is why both his detractors and supporters were in agreement about his original thesis in the flurry of reviews penned back in February, 2007.1 Indeed, without the ritual murder component this thesis borders on absurdity: how credible is it that Ashkenazic radicals regularly utilized Christian blood in anti-Christian Passover rituals but would never ever harm a Christian to obtain it?2 Clearly these are pro forma denials penned in the face of substantial pressure,3 and Toaff realizes most readers will have enough sense to simply look beyond them.

At the center of Toaff’s treatment of the case are the records of the interrogations of the Jews, which he calls “a priceless document,” indeed “the most important and detailed document ever written on the ritual murder accusation, a precious document retaining the words of the Hebrew defendants.” Still, these records are highly imperfect sources prepared by an interested party. In Blood Libel, Magda Teter notes that none of the originals survive and the extant copies contain their share of discrepancies. Some records, like those of the trial of Samuel’s wife, “have been lost even though their existence is mentioned in other sources.” (We only know that Brunetta was said to have finally signed her confession after being submerged in the urine of a virgin boy and to have died shortly thereafter.) Diego Quaglioni, an editor of the records and one of a number of scholars Toaff cites who would issue negative reviews of the book, was most vocal about these source limitations:

These texts are the result of a clever construction by the judges, by the notary: anyone who has ever had to deal with an inquisitorial trial in the late Middle Ages knows what I am talking about. Those documents in particular were artfully constructed to demonstrate the infamous theory of ritual murder. One cannot naively believe these depositions when one knows that the trial was constructed specifically to demonstrate the guilt of the Jews. … In Trento in 1475, immediately after the events and the condemnation, the Pope sent a Dominican inquisitor to verify whether the trial had been conducted regularly. He was convinced that the minutes were fabricated. … We no longer have the originals of the trials, we have copies provided to Rome by the bishop of Trento who organized the trial.

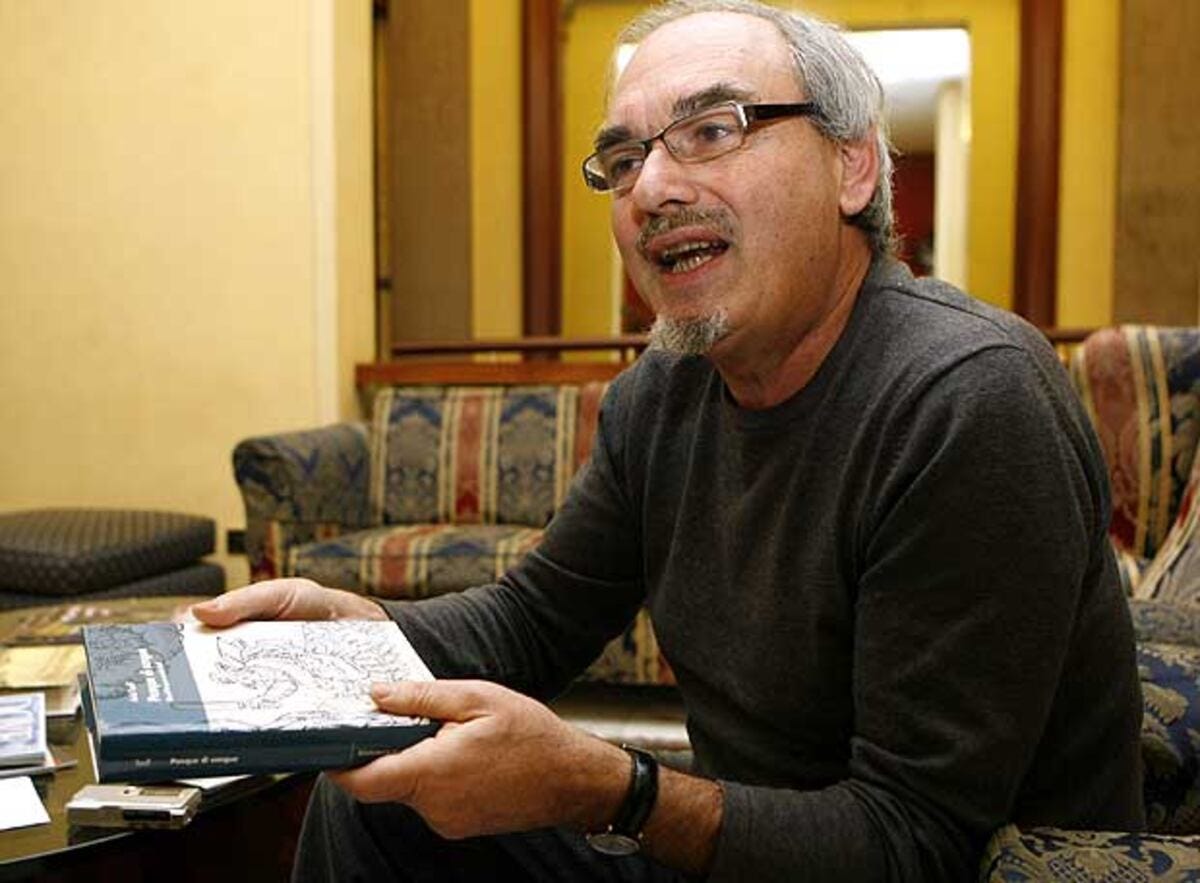

To make matters worse, throughout the book Toaff frequently draws on apologetic sources written in 1747 and 1902, centuries after the trial and “with the declared aim of supporting the cause of the sainthood of Simonino,” for which he was roundly criticized by his colleagues, though he defends their accuracy in the Afterword to the second edition. But undoubtedly the most pressing issue with the sources is their liberal reliance on judicial torture. According to Hsia:

The standard mechanism of torture was the strappado, for which the victim had his hands tied behind his back with a long rope and was then hoisted up in the air by a pulley. Left dangling several feet from the ground, the victim would thus face the judge, who was attended by the scribe recording the interlocution and the prison guard doubling as torturer. Judicial procedure allowed for the gradual escalation of torture. If the victim refused to confess, the torturer would abruptly let loose the rope (cavalete), a practice frequently repeated … If that method failed to produce the desired effect, other painful refinements were inflicted, such as whipping with the rope (squassatio) or adding weights to the feet of the dangling victim.

If the Wikipedia page is to be trusted, the physical strain from this instrument was so great that it could result in death if employed for more than an hour. Hsia offers a number of illustrations of the strappado’s effects on the Jewish defendants from his copy of the records:

the podestà [de Salis] ordered Tobias pulled all the way up ... Tobias cried out he would tell the truth and begged to be let down. “He was let down,” the scribe tells us, “and it looked like he was completely senseless or ruined. When he began to come to his senses, the podestà asked him to speak the truth.” Since Tobias could hardly speak, Giovanni de Salis adjourned the questioning until the next day.

Tortured only once initially, on 4 April, Old Moses had been languishing in his cell for more than two months when he appeared on 9 June before the magistrates. Eighty years old, his health broken by incarceration, Moses “looked dumb (bloed) in anticipation of pain,” as the clerk observed. Giovanni de Salis strung him up a bit, put two hot eggs under his armpits, and then sent the old man back to his cell.

Gruesome as this may be, the application of torture was fairly standard in medieval criminal trials and certainly doesn’t tell us anything about the guilt or innocence of the defendants, or even if what they confessed was ultimately false. Indeed, as Toaff demonstrates, at times the Jews would confess to things the interrogators could not have known about, let alone dictated, including Hebrew curses4 the stenographer would often transcribe incorrectly out of evident unfamiliarity.

In many cases, everything the defendants said was incomprehensible to the judges – often, because their speech was full of Hebraic ritual and liturgical formulae pronounced with a heavy German accent, unique to the German Jewish community, which not even Italian Jews could understand; in other cases, because their speech referred to mental concepts of an ideological nature totally alien to everything Christian. It is obvious that neither the formulae nor the language can be dismissed as merely the astute fabrications and artificial suggestions of the judges in these trials … A careful reading of the trial records, in both form and substance, recalls too many features of the conceptual realities, rituals, liturgical practices and mental attitudes typical of, and exclusive to, one distinct, particular Jewish world – features which can in no way be attributed to suggestion on the part of judges or prelates – to be ignored.

This is the logic Toaff uses to reconstruct from the confessions long-forgotten Jewish practices that incorporated the hematophagous use of Christian blood. In the later chapters of the book, he attempts to show how these alleged practices align with an interesting though highly speculative reading of Jewish exegesis and mysticism, a subject for which I lack the relevant expertise to meaningfully opine on at least for now. But the flaw in this methodology should be immediately apparent, and was noticed by most of the reviewers including, again, those authors on whom Toaff relied, like Carlo Ginzburg:

At the end of his preface, Ariel Toaff declares that he read the documents on ritual murders inspired by a methodological principle that had inspired my research many years ago on the stereotype of the witches' sabbath (Storia notturno, 1989). This is an abusive reference: Ariel Toaff followed a completely different path than mine. ... the Jews subjected to torture confessed what the judges were looking for, that is, the story of the ritual murders: there was, on this point, no divergence whatsoever between the expectations of the judges and the answers of the defendants. But those stories were inserted into descriptions of ceremonies familiar to the defendants such as, predictably, the Jewish Passover.

Thus it’s trivial for Toaff to find that “the so-called ‘confessions’ of the defendants during the Trent trials relating to the rituals of the Seder and the Passover Haggadah are seen to be precise and truthful.” It’s no surprise “[t]he judges at Trent could barely follow these descriptions,” and it’s indeed “not very plausible” that “the judges dictated these descriptions of the Seder ritual.” Toaff repeatedly frames the matter as a question of whether “these ‘confessions’ reflect merely the beliefs of Gentile judges, clergy and populace, with their private phobias and obsessions, or, on the contrary, of the defendants themselves.” “In other words, an attempt should be made to determine whether these crude and embarrassing confessions were largely the result of suggestion, and were, so to speak, recited and written under dictation.” But this is a false dilemma that frames any truthfulness on the part of the defendants as evidence of guilt.

Occasional truthfulness is in fact only to be expected from the falsely accused who, when pressed for more precise details under immense psychological pressures, would most readily volunteer what was already familiar to them and believable to the interrogators in support of the expected conclusion: in this case, that Simon was cruelly murdered in mockery of Christ, that his blood was used in the ceremonial matzoh and wine. As Anna Foa writes in her review: “to stop being tortured, the accused had to not only confess, but confess plausible things, consistent with other confessions, subject to verification.” Another reviewer pointed to the similarities between Toaff’s methods and the long-dismissed witch-cult hypothesis of Margaret Murray, who similarly argued that the confessions of accused witches tended to substantiate the existence of something close to devil-worship: “Just as the women (and men) accused of witchcraft recounted details that were often true about magical and superstitious practices, but certainly gave voice to their own or the judges’ fantasies when they told of having coupled with the Devil or of flying on broomsticks, so it is possible that the Jews tortured in Trent opened a window on a world of popular superstitions of the time, but this does not mean that what they ‘confessed’ about the ritual murder of little Simon and the assumption of his blood was true.”

Exactly how leading these interrogations were is something Toaff really doesn’t appreciate anywhere in the book. At one point Engel’s servant, Lazarus, flatly demanded his interrogators “Tell me what I should say and I will say it.” Engel’s cook, Isaac, exclaimed between bouts of torture “if I knew what I should say, I would gladly say it.” When the podestà told him he “should no longer keep silent because his accomplices have told the truth,” Samuel replied, “Even if they said something they still had not told the truth. […] Then they give him holy water and place hot eggs under his armpits and he relents.” Hsia cites another revealing exchange with Tobias’ relative, Joaff:

He was asked whether he saw the murdered boy.

JOAFF: In the ditch.

PODESTA: Think again.

JOAFF: In the antechamber of the synagogue.

PODESTA: Anywhere else?

JOAFF: No.

He was ordered stripped, tied by the rope, and hoisted up.

JOAFF: Let me down, I'll speak the truth.

PODESTA: Speak it on the ropes.

JOAFF: I have never done anything evil.

He was hoisted up and dropped. He swore by his death, which he will soon suffer, that he is innocent; he has never seen the child anywhere. . . . He did not see the child anywhere else [besides in the ditch], he would love to have seen it [elsewhere] with his own eyes. He was hoisted up again. . . .

JOAFF: I saw the dead boy in the synagogue.

He summarizes his reading of these interrogations:

Some of the Jews held out, repeating their innocence over the screams of torment and stem questions; others broke down, blaming themselves and others in this grotesque elaboration of the fictive murder ritual. Still others retracted their confessions during moments of lucidity and respite from the rope, only to be tortured more severely into retracting their retractions. A few wanted to confess but could not anticipate the murder script written in the minds of the magistrates and, thus, continued to suffer

These facts should at least reintroduce that cloud of uncertainty Toaff pretends to have evaporated—it’s genuinely difficult to identify whatever truth there may be in these confessions. Identifying falsehoods, on the other hand, is often a much more straightforward task as the resultant narrative would at times border on absurdity, clearly reflecting the projection of naive Christian beliefs onto the tongues of the Jewish prisoners. For example, the Jews confessed to requiring the blood specifically for Passover during Jubilee years, a term which has borne no religious significance whatsoever for Jews since the destruction of the first Temple in 586 BC; the only time this is even hinted at by Toaff is in the line I quoted at the beginning. Further, among the uses of Christian blood, the Jews would confess to its importance in ameliorating their foetor judaicus, or unique Jewish stench. But to my mind the most puzzling aspect of the confessions was their unanimous insistence Simon had been slain on Good Friday:

The depositions of the defendants in the Trent trial were all in agreement as to the fact that the murder of little Simon was said to have been committed on Friday, inside the synagogue, located in the dwelling of Samuele da Nuremberg, and, more exactly, in the antechamber of the hall in which the men gathered in prayer.

At the very least this is odd. Passover of 1475 had begun on Wednesday evening, and in the diaspora the ceremonial seder is traditionally held on the first and second nights. By Friday the seder was clearly over, so how could Simon’s murder have played a part in the ritual? Perhaps the real time of death was during the observance of the second seder on Thursday, the evening of Simon’s disappearance, but even still: all the uses of Christian blood for Passover that Toaff surveys demand it baked into the shmurah matzoh on the day of preparation.

The use of the blood of Christian children in the celebration of the Jewish Passover was apparently the object of minute regulation … almost as if it formed an integral part of the most firmly established regulations relating to the ritual. The blood, powdered or dessicated, was mixed into the dough of the unleavened or “solemn” bread, the shimmurim – not ordinary bread. The shimmurim – in fact, three loaves for each of the two evenings during which the ritual dinner of the Seder was served – were considered one of the principal symbolic foods of the feast, and their accurate preparation and baking took place during the days preceding the advent of Pesach. During the Seder, the blood had to be dissolved into the wine immediately prior to recitation of the ten curses against the land of Egypt.

The statements of various Jews are cited to this effect:

Samuel: “The evening before Pesach, when they stir the dough with which the unleavened bread (the shimmurim) is later prepared, the head of the family takes the blood of a Christian child and mixes it into the dough while it is being kneaded”

Tobias: “every year, the blood, in powdered form, is kneaded into the dough of the unleavened bread prepared the evening before the feast, and is then eaten on the solemn day, i.e., the day of Passover”

Angelo de Verona: “[they] take a small quantity of the blood and they put it in the dough with which they later make the unleavened bread which they eat during the solemn days of the Passover”

Ignoring the fact there are stringent rabbinical regulations about their ingredients—strictly flour and water—by Thursday these matzot had already been prepared. So what exactly is the significance of these statements? Did the Jews already have Christian blood in their possession? Was Simon’s murder simply an attempt to collect additional blood for sale or use in subsequent seders? At least from my reading of the book, Toaff never answers these questions—strange, since this has been a classic objection to the Tridentine narrative brought up in works like The Jew and Human Sacrifice (193ff) and Joshua Trachtenberg’s The Devil and the Jews.

And what was the ritual significance of this coveted Christian blood? Why would these Jews prize it so highly that they’d be willing to procure it at great risk to themselves and their families, with the memory of past retaliations so fresh in mind? Compiling all the opinions given throughout the records seems to introduce more inconsistency than coherence on this point. Naturally, the Jews associate it with everything bloody in the Exodus story. There was the blood of the lamb sacrifice, which post-Temple has traditionally been associated with the shank bone of the seder or the afikoman. Moshe, the old man of Trent, explained how

According to the laws of Moses, it is commanded of the Jews that, in the days of the Passover, every head of family should take the blood of a perfect male lamb and place it (as a sign) on the door-posts of the dwellings. Nevertheless, since the custom of taking the blood of the perfect male lamb was being lost, and, in its place, (the Jews) now used the blood of a Christian boy

Tobias on the other hand—and somewhat mistakenly, as he had a reputation of being ignorant in matters of religion—brought up how “Jews used blood to celebrate Passover when the Red Sea turned into blood and destroyed the Egyptian army.” On April 13, Israel answered that “If they don’t use blood they’ll stink,” and further that it was used “[a]fter the custom of painting blood on the post in Pharaoh’s times.” Mockery of the Passion was of course central: according to Vitale, “the Jews perform the memorial of the Passion of Christ every year, by mixing the blood of the Christian boy into their unleavened bread.” Per Angelo de Verona, “just as the body and powers of Jesus Christ, the God of the Christians, went down to perdition with His death, thus, the Christian blood contained in the unleavened bread shall be ingested and completely consumed.”

When asked about the origins of these rites—apparently unaware they’re supposed to be exclusively Ashkenazic—Samuel attributed them “to the rabbis of the Talmud (Iudei sapientiores in partibus Babiloniae), who were said to have introduced the ritual in a very remote epoch.” Further, they also “appeared in the texts of Jews from overseas.” Seeing as this contradicts Toaff’s thesis, perhaps Samuel was mistaken here, or perhaps he was muddying the waters. But the most likely explanation is that this is simply another indication of the invention of false stories to satisfy the demands of torturers.

As mentioned in the previous essay, Toaff does provide a decent amount of evidence for the penetration of the Christian blood culture into medieval, even modern Jewish practice; this is something I’d never encountered before in any other treatment of the blood libel and seems to be an important contribution of his work. Nevertheless it’s noteworthy that among all the sources he investigated, it’s only in the aforementioned confessions that there’s any mention of the usage of specifically Christian blood in Jewish remedies or rituals. Indeed the total absence of any internal Jewish references to these dealings has always posed a problem for those interested in establishing the historical truth of the blood libel, especially since this must have been a fairly widespread practice according to the statements of the Trent Jews.5

Yet not as much as a passing reference has been unearthed, despite prying eyes. In Die Polemik und das Menschenopfer des Rabbinismus, August Rohling claimed to have been aware of—but not personally possessed—an apparently quite popular sefer of 20 editions by the name “Gan Naul” (גן נעול, “closed garden”), authored by a certain R’ Mendel of Kossów (d. 1860s). Here we read of a rabbi lamenting the bloody, deviant custom, which by then had become the domain of the Ostjuden:

Rabbi Mendel in his Gan Naul teaches us that the number of zealous people who, out of religious urge, shed human blood is not very large among the Orthodox except in Hungary, Galicia and Poland in general, and protests against the fact that the blood which is shed in all countries in honor of the Orthodox should also be put into the matzoh.

Just one such reference is truly all it would take to establish the historicity of die Blutanklage. Yet it doesn’t exist. Hermann Strack referred to Gan Naul as a “gross falsification of A. Rohling’s,” and it does seem far too convenient for Rohling to cite a work he didn’t personally possess and that, at least from his description, was basically impossible to acquire:

For a long time I have been looking for a document of this kind, the contents of which I know exactly and will publish in a literal translation as soon as I get hold of the little work, which unfortunately has gone missing and which I have been looking for in vain for months despite all my research. Some Jewish booksellers replied to the order that the booklet did not exist, others gave no answer at all, and still others provided a grammatical work of the same title from Wesely [here he must be referring to Abraham Abulafia’s Gan Naul], others finally wrote: Gan Naul out of print; I met a Bohemian Jew who said he had the work, but he did not give it away.

Naturally, both Toaff and Rohling agree that these blood rites belonged to an elusive oral tradition, “for obvious reasons of prudence.” Certainly prudence and secrecy were important values for religious Jews living among medieval Christians, and Toaff offers descriptions of the careful transmission of the Toledot Yeshu, inflammatory Jewish counter-legends about Jesus, as an example. Yet the difference between the Toledot Yeshu and the matter at hand—both posing extreme danger if discovered—is obvious: we have plenty of documentary evidence for the former and none for the latter.

On the contrary, whenever the blood libel is mentioned in Jewish sources it’s met with rejection. When Toaff states in his Preface, citing an article by Yuval, that “[t]hese responses, whenever they were recorded, contained not the slightest rejection of the probative evidence” he’s completely misrepresenting his source. In the beginning of the essay Yuval describes one part of the 13th-century Ashkenazic polemic Sefer Nizahon Yashan which seems to deflect the blood accusation in an accusatory manner rather than addressing the claims directly. But this is not all even the Nizahon has to say on the matter, as Yuval clearly mentions later on:

The Christians reproach us and say that we murder their children and drink their blood. Answer them: No nation has been as strictly admonished against committing murder as we have. And this applies equally to the murder of non-Jews … We are also more scrupulous than any other nation in regard to blood. For even with meat that has been ritually slaughtered and is fit for consumption, we, nonetheless, salt it and are very careful to remove all the blood. But you libel us in order to shed our blood as David prophesied in Psalm 44.

To his credit, Toaff does mention the existence of private Jewish communications written in the wake of the Trent affair and intercepted by the Christian authorities, who transcribed their contents in the original Hebrew and Old Yiddish, apparently unable to translate those of the latter. In his Afterword Toaff explicitly recognizes this as evidence against Jewish guilt, as the letters present unequivocal rejection of the blood accusation and an interpretation of the unfortunate slander as the result of the collective sins of Israel. One, per a modern translation, describes the Regensburg blood libel: “because of our manifold iniquities, they have imprisoned Jews and have conspired with a plot and in falsehood they have made the accusation that they were guilty of the blood of thirty [a reference to Trent].” Another implores God to “have mercy and help his wretched people and the Jews of Regensburg who have suffered for our manifold iniquities from this great falsehood.” This is similarly the case, more famously, with the preserved Hebrew letters ostensibly written in the wake of the Blois ritual murder accusation of 1171.

Needless to say a very different picture emerges in the other accounts of Trent, which depict the confessions more simply as a product of imaginative coercion. Evidence in favor of this interpretation may be seen in the fact that even when the defendants first broke down and admitted to killing Simon, thus signing their own death warrants, their testimonies still diverged. Thus when on March 27 Seligman ben Mayer made his confession, he told of how Engel’s servant Isaac had abducted the boy, struck him such that he vomited blood which was then collected, and finally delivered him to Samuel’s house to be killed—a far cry from the eventual narrative in which Tobias was selected to kidnap Simon, who was then collectively murdered and pierced for blood on Good Friday. Thus, per Teter’s reading, while the earliest testimonies “showed relative consistency in telling how the body was discovered and what Jews were doing between the time of Simon’s disappearance and the discovery of his body,” they would only gradually be brought into alignment with a basically coherent narrative of guilt.

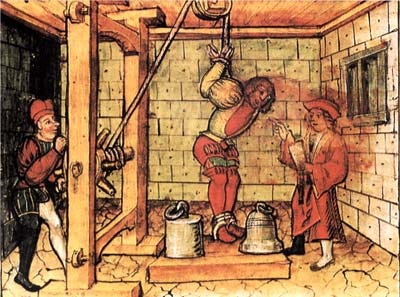

The most intriguing line of argument from Teter’s account involves the epistle of the Christian Hebraist Giovanni Mattia Tiberino to the Senate of Brescia.6 This is a violently anti-Jewish work, as is made obvious from the opening lines:

I am writing to you, Raffaele Zovenzoni, about a most important event such as no era—from the Lord's passion up to these times—has ever heard of, one which recently in these past days our Lord Jesus Christ, kindly pitying the human race and enraged by so great and so heinous a crime, has at last brought forth into the light, so that our Catholic faith, if it is weak in any respect, may become—so to speak—a tower of strength, and so that the ancient, savage race of the Jews may be eliminated from the whole Christian world, and remembrance of them utterly vanish from the land of the living.

As its title suggests, the work summarizes the woes of Simon along the lines of a Passion narrative, with Tobias playing Judas, Maria naturally Mary, etc. The Jews, coveting the boy’s blood for their obscure Jubilee rites as well as to cure their odor, kill him on Good Friday, “and lowering his head he gave up his holy spirit to the Lord.” By all accounts this letter was “the most influential piece of anti-Semitic propaganda surrounding the Trent ritual murder trial,” and it was largely through the work that the non-Italian world would become acquainted with it, something evidenced by the sheer number of editions it went through:

the first edition was published in April 1475 by Bartolomeo Guldinbeck in Rome, who brought out two more editions by July of the same year, and another in 1476. In addition to the four Roman editions, ten other Latin editions appeared in print by early 1476 … In September 1475, a German translation was published in Trent … Two more German editions appeared

Yet the entire narrative does feel suspiciously coherent given that, as Teter points out, it predates any of the confessions that would contain its details. While Seligman confessed on March 27, as has been shown this was at odds with the final narrative that would only begin to emerge on April 7. Indeed, the earliest edition of Tiberino’s letter bears the dating “Secundo Nonas aprilis, MCCCCLXXV,” that is, two days (inclusive) before the Nones of April: April 4, 1475.

And yet the letter includes highly specific information, sometimes the exact words that would be recalled by the Jews in their confessions, such as the line “On this Day of Preparation, we have plenty of meat and fish. We lack only one thing.” Even the line about Simon “lowering his head” parallels what is found on the lips of Seligman, who describes how after Simon “breathed his last … [he] died crosswise at the hour of Christ's crucifixion and hanged its head to the side” like Jesus, a totally bizarre statement that puzzles Hsia when he quotes it. As Teter puts it:

when Tiberino wrote these words, the trial of the Jews was just beginning: nothing in the existing records suggests that Tiberino’s writing was based on what he learned from testimonies of the arrested Jews. … Even if one accepts that not every thing said then was included in the records, surely if there had been even one witness or one testimony that had produced the damning details found in Tiberino’s account, it would have been included in the records sent to Rome. After all, such evidence would have made the charges against the Jews even stronger. Instead, the early testimonies weakened the case against the Jews. That changed a few days after April 4, when confessions under torture began increasingly to conform to Tiberino’s account.

Nevertheless there’s some disagreement here that Teter leaves out. The historian Wolfgang Treue, whose book I lack access to, apparently suggests the April 4 dating was falsified by the ever-tampering prince-bishop Johannes Hinderbach to bring the letter closer to the events at hand; he suggests the original dating was April 17, found on a minority of manuscripts, though Teter believes this to be just a second edition. In any event, on its face at least the argument seems damning and receives no mention by Toaff.

To stress once more, Pasque di sangue does not present a full picture of Trent, because it’s not intended to; it’s a historical illustration written to advance a fairly narrow argument, and Toaff likely, if unwisely, assumed his audience wouldn’t read it in isolation. Thus insufficient mention is made of the papal envoy, Battista de’ Giudici, who was sent on September 23 to obtain an authentic copy of the trial records and investigate the alleged murder and miracles of Simonino. At every turn, according to his own account, the Bishop of Ventimiglia was stymied by Hinderbach: delayed in receiving the records, forbidden from interviewing the remaining prisoners, even assigned a room with an open ceiling and “puddles of water, excrement, and filth,” prompting his relocation to Rovereto a month later. To Hinderbach and his allies, this was unsurprising: de’ Giudici was a suspected tool of the Jews and Rovereto was full of them.

But stooge or not, the envoy discounted all of Hinderbach’s convictions. Far from miraculously preserved, when he visited Simon’s body the stench was such that he “had an attack of cholic, not quite strong enough that I was to vomit, but enough that I could have vomited at any time.” After questioning witnesses he found the other miracles likewise “were described in a mendacious, fraudulent, and deceitful manner.” Further, his own investigations had led him to believe the real murderer was Zanesus, also known as der Schweizer, a neighbor who’d been in prior conflict with the Jews and was actually the one who advised Andreas to get the podestà to search the Jewish homes back on March 24. Not that this ultimately mattered much, since most of the Jewish males had already been burned at the stake a month before de’ Giudici arrived. Further, Pope Sixtus IV would eventually rule the trial legal in its use of torture, while still imploring Hinderbach to protect Jews from violence and, somewhat confusingly, reminding him of Innocent IV’s 1247 Decretum that unequivocally forbade the blood accusation. Simon was also not conferred beatification, though that would change a century later under Sixtus V.

The historiographical debate over the blood libel is ultimately a matter of Jewish versus Christian reference points. In a sense it’s a microcosm of the broader debate over the lachrymose conception: how much should Jewish history be understood in terms of the world of the agentic minority as opposed to that of the victimizing majority? Toaff writes the following in his Preface:

Nearly all the studies on Jews and the so-called “blood libel” accusation to date have concentrated almost exclusively on persecutions and persecutors … Little or no attention has been paid to the attitudes of the persecuted Jews themselves and their underlying patterns of ideological behavior

This, of course, hasn’t always been the case. He goes on to mention as counterexamples Israel Yuval, whom we’ve already discussed, as well as Cecil Roth from the older generation of Jewish historians, who interpreted the blood accusation in part as a Christian misperception of the unruliness of nearby Purim festivities, a theme that would be taken up by Elliott Horowitz. Others have connected the accusation with the peculiar circumcision rituals Toaff investigates, like the German custom of hanging the bloody rags at the entrance of the synagogue.

But more often than not I think Toaff would be correct in this assessment. You see this in the writing of Massimo Introvigne, cited earlier, who critiques Toaff’s thesis while still dismissing the blood libel for uncompelling reasons: firstly because of “[t]he taboo against the consumption of blood,” and secondly because “it assumes that Jews believe in the redemptive capacity of the blood of Jesus Christ,” siphoned from one of his representatives. This latter idea is very frequently the paradigm through which people understand the blood libel and other such chimerical charges: solely with respect to the Christian psychology. Folklorist Alan Dundes viewed the libel as an example of what he termed “projective inversion … a psychological process in which A accuses B of carrying out an action which A really wishes to carry out him or herself.”7 Since Christians regularly consume the blood of Christ in the Eucharist, and since they hate the Jews, the blood libel is really the projection of these beliefs onto the subject. Such psychoanalytic views of historical phenomena unfailingly have the added benefit of being impossible to actually investigate or falsify.

Indeed medieval Christians can be expected to have held naive beliefs, and many of them did feel the Jews secretly understood the true faith, refusing to convert merely out of a Satanic stubbornness. But simply dismissing Christian perceptions as misguided is still not enough to disregard the underlying accusations. In The Devil and the Jews, Trachtenberg describes a Christian belief that “whenever it happens that on the day of the Lord’s Resurrection the Christian women who are nurses for the children of Jews, take in the body and blood of Christ, the Jews make these women pour their milk into the latrines for three days before they again give suck to the children.” He waves this away as obviously spurious since, as the Christians themselves remark, it portrays Jews as such staunch believers in the Real Presence of Christ that in effect they’re “more Catholic than the Pope.” Yet superstitious aversion to perceived idolatrous objects in no way necessitates a full adoption of Christian beliefs. Alas, Yuval points to a contemporary development in rabbinical opinion urging that “[Christian] wet-nurses should be warned not to eat unkosher food and pork, certainly not unclean things,” a likely reference to the Host, whereas prior opinion had been indifferent to the diet of such persons.8 Misinterpretation by pious Christian onlookers thus bears no relation to the potential existence of what may well be, at least partly, a historically supported practice.

Clearly both Christian and Jewish perspectives need to be weighed responsibly in these matters. But it’s at least as misleading to interpret the blood libel exclusively with reference to the latter as Toaff and, albeit in a somewhat different way, Yuval do. I’ll quote David Abulafia’s review because I think he makes this point uniquely well about the overall methods of the book:

he assumes that his disparate pieces of “evidence” from Jewish sources fit together. Evidence that Jews committed acts of violence against one another or against Christians, the trade in blood, rituals of circumcision, the sacrifice of Isaac by Abraham, images of Pharaoh’s massacre of the innocents, early medieval parodies of Christianity, rowdy celebrations of Esther’s victory over Haman at the festival of Purim, are all woven loosely together; meanwhile, highly relevant Christian material, notably the surge in accusations of host desecration, and the friars’ campaigns against the Jews, is hardly addressed. … the significance of blood in Christian culture, and in particular the significance of the Eucharistic sacrifice, is largely ignored as an explanation of the fantasies

As far as I could tell, the extent to which Toaff discusses the Christian side is confined to a description of Hinderbach, a man so antisemitic he’d countenanced literally cannibalizing Jews in the past.9 As a direct result of this limited treatment, Toaff’s reader and perhaps the man himself fail to consider just how strong the case for Christian projection truly is. ✦

Continue to Part III: “How the Blood Libel Was Born”

Sources

Ariel Toaff’s Pasque di sangue. Ebrei d'Europa e omicidi rituali; an unofficial English translation can be found on the Internet Archive

Magda Teter’s Blood Libel: On the Trail of an Antisemitic Myth

Ronnie Po-chia Hsia’s Trent 1475: Stories of a Ritual Murder Trial

Without explanation Toaff states in the Afterword that “[w]e may immediately dismiss the hypothesis, even if only theoretical, that the Jews (in Trento or elsewhere) committed atrocious crimes to obtain the blood of a Christian infant and celebrate the Passover rites.” He claims the blood instead “originated from unknown ‘donors,’ alive and well.”

The ordeal is recounted at length in Loriga (2008), and is incredible really. Toaff suspended publication after being roundly condemned by Abraham Foxman, rabbi after rabbi, even the Knesset, with some MKs calling for his prosecution. He eventually ceded his royalties to the ADL "so as to express my profound regret."

At least one of these curses, however, which Toaff partly examines in earnest as corrupted Hebrew, appears to actually be a jumbled version of Psalm 20:7–8 of the daily prayers as if the Jewish subject really was just offering up unrelated Hebrew to satisfy the authorities; see Teter (2020, 58).

Moshe, for example, mentioned how “up to the time when he had been the head of a family in various places in Germany, it had been considered obligatory to provide blood for the Passover rites”; Christian blood would also be provided free of charge for indigent families. Further, if a portion of the historical ritual murder accusations have truth to them, we can only assume they represent a minority of the true number of incidents, the greater part of which were successfully concealed.

“Passio beati Simonis pueri Tridentini.” A full translation can be found in the work “On Everyone's Lips”: Humanists, Jews, and the Tale of Simon of Trent by Bowd and Cullington.

From Dundes’ The Blood Libel Legend: A Casebook in Anti-Semitic Folklore

See Yuval’s “‘They tell lies: you ate the man’: Jewish Reactions to Ritual Murder Accusations”

Hinderbach “had not hesitated to express his self-satisfied approval of cannibalism, when the victims were Jews. During the military confrontation between Venice and Trieste in 1465, during which Friedrich III intended to enforce his rights, Hinderbach, who was then acting as imperial ambassador before the government of the Serenissima, sang the praises of the Hapsburg militia, called upon to defend Trieste, for their courage and their demonstrated loyalty to the Emperor. By true right, observed the pious bishop, the German soldiers, in case of necessity, rather than lay down their arms, were to alleviate their hunger by eating the flesh of cats, rats and mice; and even that of local Jews, Jews resident in the city.”

What's missing in all this is the prohibition of murder 😅. Forget about the fact some fringe traditions permitted blood for ritual use, did any permit murder of children? And did any opinion ever specify the need for Christian blood? Why would any religious Jew see idolater blood as holy? A non-Jew can't even touch wine or cook for a Jew.

Unz also pushed the Toaff nonsense, distorting it even more: https://www.unz.com/runz/american-pravda-oddities-of-the-jewish-religion/