How the Blood Libel Was Born

Why do these images exist? Part III of "The Blood Libel and Historical Revisionism"

The following is the final part of a trilogy on the blood libel; see Part I and Part II

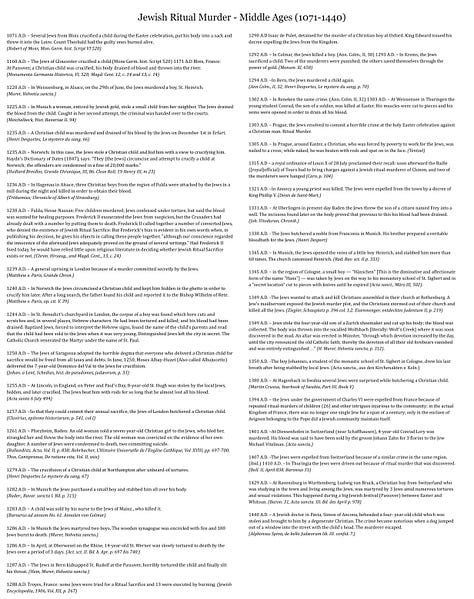

For those not relying on the more abstruse arguments of Ariel Toaff, the most common defense of the blood libel’s reality is a historical one. Namely, the sheer number of nearly identical accusations over the centuries is most naturally explained by the guilt of the accused, like independent witnesses corroborating each other’s testimony. Far from being the kind of logic you’d only encounter online, this is a classic argument that dates back at least to the writings of Johannes Eisenmenger, the notorious false convert whom Rohling plagiarized in Der Talmudjude. Thus, the compilations of alleged Jewish ritual murders that circulate around the Internet rely on pamphlets sometimes hundreds of years old.

Yet as is made clear with a basic familiarity with the early history of the blood libel, the assumptions this argument relies on are all backwards. Far from anything analogous to unrelated witnesses reporting the same crime, the libel in fact mutated considerably as it steadily diffused across Europe. The following summarizes the case for its interpretation as pertaining to the realm of myth and persecution.

The Christian Context

While the subsequent Jewish hostilities Yuval mentions are likely still relevant, the Rhineland massacres obviously reflect something significant about independent changes in the Christian attitude toward Jews. As a standard historical account1 affirms:

On the whole, Jews in early medieval Europe were permitted to live in relative security, and there is little evidence that the masses resented this state of affairs. At some point in the eleventh or twelfth century, a shift toward increased hostility gathered momentum.

It’s an incredible fact that “[d]uring the twelfth century, more Christian polemical treatises were written against the Jews than in all the preceding Christian centuries combined.” A number of factors have been raised to explain this trend, such as, most glaringly, the millenarian fervor of the Crusades of 1096–1291. Robert Chazan also notes “a transition from commerce as the mainstay of Jewish economic life to moneylending as the key to economic viability … from approximately the mid-twelfth century onward.” Others mention “the demographic explosion, social differentiation, the war of investitures, [and] the various religious popular movements—legitimate and heretical—since the eleventh century, of which the First Crusade was a part.”2

Importantly, RI Moore notes that this hostility was non-specific to Jews, expressing itself simultaneously in the treatment of the other minorities of Christian society beginning in the 12th century, namely heretics and lepers. As he puts it,

That three entirely distinct groups of people, characterized respectively by religious conviction, physical condition, and race and culture, should all have begun at the same time and by the same stages to pose the same threats, which must be dealt with in the same ways, is a proposition too absurd to be taken seriously. The alternative must be that the explanation lies not with the victims but with the persecutors. What heretics, lepers and Jews had in common is that they were all victims of a zeal for persecution which seized European society at this time.

Any anti-Christian malice the Jewish minority may have felt or expressed as such only contributed to a cycle of hostility fundamentally driven by the underlying occurrences in the Christian world Moore terms The Formation of a Persecuting Society. This would inevitably find expression in Christian culture, and in a medieval context so dependent on superstitions and Biblical typologies it’s only expected that perceptions of Jews and heretics would become so “chimerical.” An example of this, more trivial than the blood libel, was the belief in Jewish male menses that began in the early 1200s. Combining the theological inheritance of the “blood curse” of Matthew 27:25 with premodern medicinal ideas and the typological curse of Eve, many contemporary Christians were genuinely of the belief that Jewish men were cursed to menstruate like women or otherwise suffer some sort of “bloody flux” for their betrayal of the Christ.

Naturally this myth linked up well with the concurrent blood libel; you run into it often. Sometimes, as was the case in Tyrnau (1494), Jews would “confess” to requiring Christian blood for its amelioration:

When the reasons for the perpetration of such a horror were ascertained from the old men by the agony of tortures, it was found there were four reasons why the Jews at Tyrnau at that time and elsewhere had often made themselves guilty in a criminal way. Firstly: They were convinced by the judgment of their ancestors that the blood of a Christian was a good remedy for the alleviation of the wound of circumcision. … Thirdly: They had discovered, as men and women among them suffered equally from menstruation, that the blood of a Christian is a specific medicine for it, when drunk.

The Dominican friar Rudolf von Schlettstadt in the early 14th century went so far as to claim to have personally “heard from Jews that certain Jews—descended from those who cried out before Pilate at the time of Christ's passion ‘his blood be upon us and on our children’—flow every month with blood” curable only through “the blood of a Christian who has been baptised in the name of Christ.” These were the kinds of fanciful myths entertained even by members of the day’s upper classes.

Concepts like the blood curse would also frequently be drawn upon in the dissemination of the blood libel. Even more relevant was the cult of the Holy Innocents, Bethlehem’s infant victims of Herod’s slaughter described in Matthew 2:16. According to the Gospel account, all of the town’s young boys were slain on the orders of the Jewish king after he’d learned of the birth of Christ, foreshadowing Jewish involvement in the crucifixion. One could easily interpret the scene as innocent boys killed by the Jews in Christ’s place, exactly like the later martyrs, and in fact “exegetes from the eighth century to the thirteenth … read the scene [paradoxically] as a narrative about Jewish anger and Christian suffering, wherein the Innocents [were] witness to a violent Jewish hatred of Christ that begins with his birth and extends to the contemporary persecution of the saints.”3 The blood libel thus didn’t emerge out of nowhere, but was in many ways anticipated by earlier developments in the Christian culture. Then a body was discovered in Norwich.

St. William of Norwich

William was a 12-year-old apprentice in Norwich, England. On Holy Monday, March 20, 1144, a man presenting as the Archdeacon’s cook brought him to his mother, Elviva, requesting his labor in the kitchen. While reluctant, Elviva consented after receiving a paltry sum; employment in the kitchen was after all an enviable occupation at the time. Instead, William was taken to a Jewish home where he stayed peacefully for a time, only to suddenly be seized, gagged, subject to “all the tortures of Christ,” and then crucified; his corpse was discovered by a forester in Thorpe Wood on Holy Saturday. That is, at least according to The Life and Passion of St William, Martyr of Norwich by Thomas of Monmouth, the only detailed primary source for the incident.

Multiple reviewers took issue with Ariel Toaff’s credulous presentation of this narrative, as well the others depicted in chapter 7 of Pasque di sangue. According to David Abulafia, “[w]hat is disconcerting is how here and elsewhere he tells these stories in the past-indicative mood without the usual qualifications one would expect from a historian writing in Italian.” Hannah Johnson agrees that “Toaff’s review of this early accusation of ritual murder, conducted largely in the indicative, sounds like a simple recitation of events, not an account founded on moments of historiographical contention.”

And it’s hard to disagree with these concerns: as a source, The Life is even more limited and biased than the trial records of Trent. As its title suggests, this is an explicitly hagiographical account written to affirm William’s veneration as a local saint, tailoring his life to align with Christ’s Passion much like Tiberino’s epistle. Five of its seven volumes serve to document all the reported miracles, and we’re told such things as his mother received a vision foretelling his martyrdom 12 years in advance, his body was discovered thanks to a heavenly ray of light, etc. Accounts of Norwich other than Toaff’s usually mention the fact that, unlike the other leading towns and monasteries, Norwich Cathedral lacked a patron saint with which to distinguish itself and encourage lucrative pilgrimages and had unsuccessfully attempted claiming other figures in the past, suggesting a reason monks like Thomas took such an interest in the affair.

But the most important detail that doesn’t make it into Pasque is the fact that whatever happened in Norwich was not an open-and-shut case even among the city’s Christians. There in fact existed enough skepticism of Thomas’ claims to prompt a second volume of the work, penned indignantly as “an answer to those who disparage his sanctity” and serving as a defense of Volume I against its critics and their “verbose chatter.” These skeptics accused Thomas and his fellow promoters of the William cult of having “struck the stamp of truth on untruths or hav[ing] dressed up events with figments of the imagination” and questioned both the boy’s cause of death and his elevation to sainthood. In section viii of the same volume—“A warning to those who dismiss the miracles of Saint William, and who deny or doubt that he was killed by the Jews”—Thomas presents their position as follows:

“We are sure of his death, but by whom, why or how he was killed we doubt entirely; hence we would not presume to say he is a saint or martyr. And since suffering does not make a martyr, but rather its cause, even if it is shown that he was killed in punishment by the Jews or by others, who would believe beyond doubt that in life he desired to die for Christ or that he suffered death patiently for Christ when it was inflicted?”

We’ll never know exactly what the basis of this skepticism was; it was Thomas who wrote the history, and it was Norwich’s monks who ensured The Life was all that was transmitted to future generations and the monasteries abroad. Yet the narrative we’re left with is not without its curiosities. William’s body is described as having displayed evidence of torture, but the wounds weren’t necessarily indicative of crucifixion: the monks, when they examined it long after the initial burial, described only the left side as being pierced. Thomas rationalizes this as the Jews simply being prudent lest the body be discovered. And sure enough it was, albeit 1. in a forest on the opposite side of Norwich’s Jewish section,4 and 2. hanging from a tree, as if the Jews in fact wanted it to be found. EM Rose suggests William may have been a victim of the roaming bands of outlaws taking advantage of the ongoing Civil War,5 who tortured victims in similar ways, but of course we’ll never know.

After Norwich

In some ways, England might be an expected origin point for the blood libel-as-myth given their inexperience with Jews, who’d after all only arrived on the island in small numbers following the Norman conquest of 1066, or given existing traditions among Anglo-Saxons who “in the tenth and eleventh centuries … developed a number of cults of boy saints, including those of St. Æthelberht and Æthelred of Ramsey, Æthelberht of Hereford, and Edward the Martyr.” Indeed William’s death seemed to coincide with long-standing martyrological themes; Rose notes that “[t]he Anglo-Saxons had a long tradition of associating sudden violence with holy death” and had “long maintained a fascination with sexual purity and the innocence of youthful martyrs.” But England would probably not be the expected origin of the blood libel-as-fact since the great majority of European Jews were located elsewhere—if we’re bypassing Spain then mostly in Germany.

Further to this point, this wasn’t just a one-time fluke. When ritual murder accusations are arranged chronologically, a distinct pattern of dissemination from England appears, reflecting the rumor’s geographic diffusion by way of trade, travel, and relic tours. After Norwich (1144), incidents begin to appear throughout England: in Gloucester (1168), Bristol (1180), Bury St. Edmunds (1181), Winchester (1192), Lincoln (1202), and so on. It crosses the English channel into northern France by the 1170s, or perhaps 1160s: possibly to Épernay and Joinville, to Blois (1171), and to Pontoise (1163, 1170, or 1179) with the boy Richard of Paris, buried in the Church of the Holy Innocents, before the expulsion of 1181–1198. From Jewish sources we’re told of accusations along the Rhine starting in the 1180s: in Boppard (1180), Mainz (1187), and Speyer (1196).6 Far from appearing sporadically throughout the population centers of Ashkenazic Jewry as Christians independently discover a nascent ritual, things seem more predictable.7

It’s impossible to ever truly know what really happened in any of these early cases. In Johnson’s view, all the historical accusations including Trent are plagued by indeterminacy, allowing for various lines of speculation among historians. Alleged witnesses can’t be reinterviewed, alleged evidence can’t be reinvestigated, and this indeterminacy naturally becomes even more true the further back we go. With Norwich as the one exception, sources for the earliest recorded incidents are especially scarce, credulous, even contradictory. For some, a mere few lines are all that remains, with just a single line left for the boy Robert of Bury St. Edmunds; undoubtedly others were completely forgotten. As Ronnie Po-chia Hsia writes:

Sources on these alleged ritual murders before the mid-fifteenth century are few and unreliable; the chronicles that recorded these cases are generally inaccurate, uncritical, and deeply biased as historical sources. Often only a few lines of information describe a purported ritual murder. The medieval chronicles depict a scenario far removed from the actual historical reality … they provide insufficient context for the analysis and interpretation of these persecutions.

The case of Hugh of Lincoln, the most famous English incident, is a good example of these source limitations. The story comes to us from the chronicler Matthew Paris: Hugh is kidnapped on June 29, held for 10 days as all the English Jews gather in Lincoln—officially for an important wedding—and then tortured and disemboweled for purposes of sorcery. The boy’s frantic mother, upon learning he was last seen entering a Jewish home, discovers his corpse in the home’s draw well. For centuries, this was the established narrative. As recently as the early 20th, tourists were directed to the very well of Paris’ description, the boy’s initial resting place, until it was discovered in 1928 to have actually been a far newer installment. (The question of why the Jews would store a mutilated corpse in their source of drinking water apparently went unasked.)

But as explained in Gavin Langmuir’s “The Knight's Tale of Young Hugh of Lincoln,” this account is strikingly divergent from the other contemporary and more reliable sources of information on the incident, which allege Hugh disappeared on July 31, was martyred on August 27, and then discovered shortly thereafter. Regarding the well, while they all mention the body being discovered in one, none actually claim it was in a Jewish home or that it otherwise implicated the Jews. If anything it was said to be intentionally far from Jewish residences—to deflect suspicion, of course—and there’s no mention of disembowelment either. Despite their differences, all accounts describe the miraculous: the Jews are depicted futilely disposing of the body in various farcical ways, with it being tossed back up by the water or the earth each time. The draw well they finally settled on was then revealed to Christians by a beam of light à la William and many other English martyrs. As one can imagine, sources like this were well-suited for preserving local fantasies and ultimately transforming them into larger phenomena.

After all corpses do occasionally turn up under unclear circumstances, and the common people may attribute undue significance or even miracles to them. Rose relates one revealing account by Guibert of Nogent, penned some 20 years before, but in many ways quite similar to, Norwich:

I have indeed seen, and blush to relate, how a common boy, nearly related to a certain most renowned abbot, and squire (it was said) to some knight, died in a village hard by Beauvais, on Good Friday, two days before Easter. Then, for the sake of that sacred day whereon he had died, men began to impute a gratuitous sanctity to the dead boy. When this had been rumored among the country-folk, all agape for something new, then forthwith oblations and waxen tapers were brought to his tomb by the villagers of all that country round. What need of more words? A monument was built over him, the pot was hedged in with a stone building, and from the very confines of Brittany there came great companies of country-folk, though without admixture of the higher sort. That most wise abbot with his religious monks, seeing this, and being enticed by the multitude of gifts that were brought, suffered the fabrication of false miracles.

As news of ritual murder began to travel, increasingly the local Jews would be the ones to stand accused in a kind of “Jew of the gaps” fallacy. As described in the Hebrew account of Blois (1171), “it was becoming common, when a body was found in cities or the countryside, for Jews to be accused of the crime.” In his defense of the Jews of Germany, Pope Innocent IV would write that “[n]o matter where a dead body is found, their persecutors wickedly throw it up to them.” Indeed in most early cases a body is all there was, as we saw with Lincoln (1255). In the case of Harold of Gloucester (1168), the boy apparently disappeared on February 21 and was fished out of a river on March 16. As was the case in Lincoln, a recent gathering of Jews, officially to celebrate a circumcision, is noted to have caused suspicion. The chronicler continues, rather amazingly:

It is true no Christian was present, or saw or heard the deed, nor have we found that anything was betrayed by any Jew. But a little while after, when the whole convent of monks of Gloucester and almost all the citizens of that city, and innumerable persons coming to the spectacle, saw the wounds of the dead body, scars of fire, the thorns fixed on his head, and liquid wax poured into the eyes and face, and touched it with diligent examination of their hands, those tortures were believed or guessed to have been inflicted on him in that manner. For at length it seemed that he had been placed in the middle of two fires and they burnt his sides, his back, his buttocks, together with his knees and hands, also the soles of his feet. They fixed the thorns around the circumference of his head, and under both eyes, and as the fat blazed up as roasted meat customarily does, it dripped down drop by drop over the whole surface of his body. Also the wax which had been put in his eyes and ears turned liquid, his neck was twisted and his incisor teeth had been knocked out. It was like a body which was soon afterward found to be liquified. It was clear that they had made him a glorious martyr to Christ, being slain without sin, and having bound his feet with his own girdle, threw him into the river Severn.

At Blois (1171), there wasn’t even so much as a body. The accusation which led to the burning of almost all Blois Jews was rather based on the testimony of a servant who claimed to see a Jew dispose of a Christian (?) child in the Loire, subsequently passing an “ordeal by water” to confirm his truthfulness. In 1202, the Lincolnshire Assize records the Jews being blamed for the corpse of a boy with a wound in his side found in a cave. In Boppard, a Christian crew found the body of a young girl on a riverbank, accused the Jews of the vessel ahead of them, and, as they refused baptism, drowned them in the river. In Speyer, the local Jews were accused upon the discovery of another girl’s corpse outside the town walls. That’s typically how it went, and it’s hard to argue with Langmuir’s conclusion about Lincoln: “Had the fantasy of ritual murder never developed, young Hugh would have remained but one of thousands of unrecorded victims of homicide or accidental death.” Indeed, had the fantasy already developed, Beauvais would likely have gone down as yet another incident of Jewish ritual murder.

Shifting Archetypes

It’s important to clarify that this rumor that was only beginning to grip Western Christendom was not quite the blood libel yet—that is, the sacrifice of a Christian child on Passover and the ritual consumption of their blood—and many key elements of the classic form are missing. A large number of the early cases didn’t even occur on Passover. Harold of Gloucester, for example, disappeared and was discovered before either Passover or Easter had begun, on March 26 and April 9 respectively (per the Julian calendar). Lincoln (1255), as we saw, was in the summer, despite Matthew Paris very deliberately describing the boy’s killing as quasi ad Paschale sacrificium, “as if a Passover sacrifice.” As they’re certainly not in fact Passover sacrifices, it’s quite difficult to conceive of these cases as anything other than fabrications.

Yet as is plainly reflected by Paris’ comment, a rumor can exist even in express contradiction to the evidence. And in the 12th century, while still inchoate, the rumor against the Jews seemed to involve the crucifixion of Christian boys during if not strictly Passover then the Easter season broadly. According to Langmuir, we see this description in Robert of Torigny, for example, who

recorded that many Jews of Blois had been burned in 1171 because they had crucified some child during the Easter season. He immediately went on to note that they had done the same in Stephen’s reign to St. William at Norwich, where many miracles had occurred, to some other person [Harold] in Gloucester in Henry II’s reign, and to St. Richard [of Pontoise], at whose tomb in Paris many miracles had occurred. “And frequently, it is said, they do this in Easter season if they find the opportunity.”

Similarly, the monk Rigord of St. Denis writes that King Philip II (b. 1165)

had heard many times from the children who had been raised with him in the royal palace—and had carefully committed to memory—that the Jews who dwelt in Paris were wont every year on Easter day, or during the sacred week of our Lord’s Passion, to go down secretly into underground vaults and kill a Christian as a sort of sacrifice in contempt of the Christian religion. For a long time they had persisted in this wickedness, inspired by the devil, and in Philip’s father’s time many of them had been seized and burned with fire. St. Richard, whose body rests in the church of the Holy-Innocents-in-the-Fields in Paris, was thus put to death and crucified by the Jews, and through martyrdom went in blessedness to God. Wherefore many miracles have been wrought by the hand of God, through the prayers and intercessions of St. Richard, to the glory of God, as we have heard.

The rumor even finds expression in the Castilian legal code, Las Siete Partidas, in 1265, whose authors “have heard it said that in some places Jews celebrated, and still celebrate Good Friday, which commemorates the Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ, by way of contempt: stealing children and fastening them to crosses.” In this early interpretation, the emphasis seems to be less on Passovers of blood and more on the Passion of the Christ, depicting a mockery of Christianity more than mysterious Jewish religious needs and thus sticking to the Christian rather than the Hebrew calendar. Of course in the Christian mind, the Jews were simply reliving their singular role in the Passion narrative recounted during Holy Week.

This isn’t to mean that the early rumor was never associated with the Jewish Passover. According to the chronicle of Rabbi Eleazer ben Judah, in 1187 the Jews of Mainz stood accused of murder and were forced to swear “they do not kill any Gentile on the eve of Passover.” Thus, Trachtenberg goes a bit too far in writing,

The earliest explanation of these alleged crimes, therefore, which was widely accepted for a while, held that the Jews crucified Christian children, usually during Passion week, in order to reënact the crucifixion of Jesus and to mock and insult the Christian faith. Every one of the twelfth-century charges was based upon this motif [italics in original]

Yet even when it comes to that first charge in Norwich, Thomas of Monmouth himself claims the martyrdom took place on Passover—which he incidentally misdates by two days—possibly as part of his representation of William as the Paschal lamb like Christ. Nevertheless, the evidence suggests this detail was left out entirely in transmission. The nearby Anglo-Saxon Chronicle from 1155 writes that “the Jews of Norwich bought a Christian child before Easter and tortured him with all the torture that our Lord was tortured with; and on Good Friday hanged him on a cross on account of our Lord,” and the few other contemporary references to William outside of Norwich likewise date the martyrdom to Good Friday, the day before the discovery of the body, a day that also marks the killing of Christ. Even the commemorative feast of St. William celebrated for a time at Norwich Cathedral was set to Good Friday according to its calendars, not Holy Wednesday as Thomas would have it.8 Notwithstanding these two exceptions, an association with Easter rather than Passover dominates the 12th-century accusations.

The Blood Accusation

But the most striking difference with the eventual blood libel was the conspicuous lack of blood in these early accounts. In Norwich there’s no reference to any ritual let alone cannibalistic use of blood. In The Life Thomas cites an unnamed Christian maid who was for some reason allowed to bear witness to William’s killing but admittedly didn’t come forward until Thomas sought her out years later. Yet she recalls being ordered to fetch a pot of boiling water specifically “in order to staunch the blood and to wash and close the wounds,” contrary to the assiduous draining and collection of blood in later stories. In none of the primary sources for any of the other early incidents is there a bona fide blood accusation to be found, either.

Yet at some point the narrative changes. Langmuir writes,

From 1150 to 1235, the ritual murder accusation against Jews was that they annually crucified a Christian boy to insult Christ and as a sacrifice. In 1235, a second type of ritual murder accusation appeared by itself or in conjunction with the older accusation, that Jews killed a Christian child to acquire blood they needed for their rituals or medicine.

The occasion is Fulda, Germany—on Christmas of all times—when the local Jews are accused of killing and collecting the blood of five Christian boys to use ad suum remedium; the two sources unfortunately don’t mention why. Nevertheless this was a major event, as the enraged Fuldans would demand Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II take action against the Jews of his jurisdiction. According to the golden bull of 1236, the Emperor did in fact launch an investigation into Jewish usage of Christian blood in parasceve—apparently an ecclesiastical Latin term for Good Friday—after recognizing that on account of Fulda “a menacing public opinion arose generally against the rest of the Jews in Germany.” After consulting with his advisors, trusted converts were requested and sent in from various European principalities. Reflecting the still-bloodless nature of the English accusations, Henry III commented in his reply that “he would gladly send two of his most trustworthy converts … but a case like that of Fulda was unheard of in England.” The resulting council’s eventual ruling is recorded as follows:

Neither in the Old nor in the New Testament is it found that the Jews are greedy for human blood. Rather it is expressly stated in complete opposition to such an assertion in the Bible, which is called in Hebrew “Bereschith,” in the laws given to Moses, in the Jewish ordinances, which are called in Hebrew Talmud, that they must altogether beware of pollution with any blood whatever. We add, and it is an addition which concerns us very closely, that those who are forbidden the blood, even of the animals allowed them, cannot have any thirst for human blood, because the horror the thing, because nature forbids it, and because of the relationship of species which connects them also with the Christians ... and that they would not expose their property and life of peril.

On that basis, Frederick II formally defended his Jewish subjects: “We have therefore with the agreement of the Princes declared the Jews of the before-mentioned place to be entirely acquitted the crime attributed to them, and the rest of the Jews in Germany of so grave an accusation.”

Yet the blood accusation would obviously not die with Fulda. When it arrives in Valréas in 1247, we find the emergence of the bloody Passover narrative at last, though the matzoh motif would only arrive later in the century. A mere five years after Fulda was the Disputation of Paris, an event that launched the concept of rabbinical law into Christian consciousness, radically undermining the notion of Jews as strictly an Old Testament people and as such their standing in Christian society.9 It’s no surprise then that Valréas offers the first explicit connection of ritual murder to innate Jewish practice; according to the contradictory confessions extracted via torture from the Jewish suspects, oddly accused of murdering a Christian girl, the victim was supposed to have been sacrificed on Good Friday with her blood poured out like a Temple sacrifice, something frequently practiced by the Sephardic Jews of Spain.

This particular persecution was so egregious that it prompted the intervention of the Pope, who decried “Christians, who, covetous of their possessions or thirsting for their blood, despoil, torture, and kill them without legal judgment, contrary to the clemency of the Catholic religion.” With respect to the local authorities, he then ordered the Archbishop to “cause them to restore the said Jews to their former liberty, and to render due satisfaction to them without any hindrance whatever, as they shall upon due reckoning be held liable for the property stolen and for the damage done.” Months later, Innocent IV described receiving another “tearful plaint of the Jews of Germany that some princes, both ecclesiastical and lay, and other nobles and rulers of your districts and dioceses are plotting evil plans against them and are devising numerous and varied pretexts so as to rob them unjustly and seize their property.” Four days later he would reissue Sicut Judeis, the papal bull of protection for the Jews, with the following addition:

nor shall anyone accuse them of using human blood in their religious rites, since in the Old Testament they are instructed not to use blood of any kind, let alone human blood. But since at Fulda and in several other places many Jews were killed because of such a suspicion, we, by the authority of these letters, strictly forbid the recurrence of such a thing in the future. If anyone knowing the tenor of this decree should, God forbid, try to oppose it, he shall be in danger of loss of honor and office, or be placed under a sentence of excommunication, unless he makes proper amends for his presumption. We want, however, that only those be fortified by this our protection, who dare plot nothing against the Christian Faith

This was the Decretum that Pope Sixtus IV would remind Bishop Hinderbach of, but this stance would change over time. The “last papal defense of Jews against such accusations was in 1540,” and the Church would ultimately beatify both Simon of Trent and Andreas of Rinn. When Cardinal Lorenzo Ganganelli—later Pope Clement XIV—was tasked with investigating a contemporary wave of blood libels, he found them all to be without basis, excepting only, in line with Church policy, Simon and Andreas.

For the above reasons, historians typically don’t refer to cases like Norwich as blood libels, favoring terms like ritual murder or crucifixion. While the charge has roots in the 12th century, the “blood libel” as such really only emerges in the 13th. Yet as much as this change was temporal was it geographical. Even though the charge of ritual murder arose there, Darren O’Brien writes that “before their expulsion in 1290, Jews in England were not accused of blood libel” proper, which would mostly circulate in the Germanic lands.

But it’s also well-established that this was a century of theological change for the Christian culture at large which was witnessing a growth in devotion to the Eucharist, perhaps partly in reaction to an increasing heretical skepticism toward the Real Presence of Christ as Langmuir has suggested.10 As such, it was the Fourth Lateran Council of 1215 that established the doctrine of transubstantiation with its first canon; the Feast of Corpus Christi was ordained soon after. It was also at this time that the cultic adoration of the Host develops as a popular form of piety, and in general there was a heightened sensitivity to the potency of Christ’s body and blood. According to Caroline Bynum’s Wonderful Blood, it was the blood in particular that would become “the central symbol and central cult object of late medieval devotion.” Cults of the Holy Blood, commemorating alleged Eucharistic miracles, would flourish in Germany especially.

The Jesuit Father Peter Browe who studied the cult of the Eucharist and its related phenomena in the Middle Ages compiled a thorough list of documented blood miracles from all over Western Europe from around 1200 to 1500. It is striking to see that of the 140 miracles cited by Browe more than half occurred in German speaking countries

These developments could plausibly explain why not just the blood libel but the other blood myths like male menstruation and host desecration all appear in the same century: as the Christian milieu developed, growing increasingly bloody, so did the Christian perception of the Jew.

Chimerical Slanders

In effect what we see in the early history of ritual murder is the transmission of a myth from England both geographically and conceptually, with incidents conforming substantially to the Norwich tale before hardening as the familiar blood libel in tandem with independent changes in the Christian milieu. Such a thing is certainly not without precedent, especially given the similarly chimerical charges being levied against the other religious minorities at precisely the same time. As Norman Cohn notes in Europe’s Inner Demons, when the first real wave of persecution against the heretics of Western Christendom began in the 11th century, it relied on slander at least as much as physical force: “heretics were not only burned, they were defamed as well.”

The kind of defamation employed could be quite creative, at least in the manner of a child telling spooky stories on Halloween. In Vox in Rama, a 1233 bull issued by Pope Gregory IX, we read of a colorful induction ceremony:

Usually there first appears a toad, which the novice has to kiss either on the behind or on the mouth; though sometimes the creature may be a goose or a duck, and it may also be as big as a stove. Next a man appears, with coal-black eyes and a strangely pale complexion, and so thin that he seems mere skin and bone. The novice kisses him too, finding him cold as ice to the touch; and as he does so, his heart is emptied of all remembrance of the Catholic faith. Then the company sits down to a feast. At all such gatherings a certain statue is present: and from it a black cat descends … [After the anticipated orgy] a man comes out from a dark corner, radiant like the sun in his upper half, but black like a cat from the waist down. The light streaming from him illumines the whole place. The master presents this man with a piece of the novice’s garment, saying, ‘I give you what was given me.’ The shining man answers, ‘You have served me well, you will serve me better still. What you have given me I leave in your care.’ And then he vanishes.

But very often the stories were more generic, borrowing from recycled types like “the orgy” or “the Thyestean feast” in a lazy attempt at discrediting a religious rival by means other than argument. As a social phenomenon this kind of thing has a long and well-understood history. The pagan slander of the early Christians is one such example in which we find a powerful analogue to the eventual Jewish one. Here we find the same accusations of infanticidal blood rites, now surviving in the texts of the Christian writers of the period. Very often the writers plead their innocence, as this was truly a widespread problem “flourishing in all the main areas where Christians were to be found—north Africa, Asia Minor, Rome itself; and not only amongst the unlettered populace, either.” As Tertullian laments:

We are said to be the most criminal of men, on the score of our sacramental baby killing and the baby-eating that goes with it … Look, then; we offer a reward for these crimes; they promise eternal life! For the moment believe it. Then I ask a question on this point—whether even you, sir, who have believed it, count eternal life worth winning at such a price, with all this on your conscience? Come plunge the knife into the baby, nobody’s enemy, guilty of nothing … catch the infant blood; steep your bread with it; eat and enjoy it.

Menucius Felix describes another such charge:

As for the initiation of new members, the details are as disgusting as they are well known. A child, covered in dough to deceive the unwary, is set before the would-be novice. The novice stabs the child to death with invisible blows; indeed he himself, deceived by the coating dough, thinks his stabs harmless. Then—it’s horrible—they hungrily drink the child’s blood, and compete with one another as they divide his limbs.

Here we also find false confessions, as was the case in AD 177 in Lyons when the slaves of Christian prisoners were tortured into confessing “that their masters killed and ate children and indulged in promiscuous and incestuous orgies.” Justin Martyr asks,

What man, greedy of pleasure or intemperate, and finding satisfaction in the eating of human flesh, would call indeed death welcome and would not sacrifice everything in order to continue his usual mode of life unobserved and as long as possible? If you have extorted by means of tortures some single confessions from our slaves, wives and children, they are no proofs of our guilt.

Eusebius relates the story of one such tortured Christian:

But the devil, thinking that he had already consumed Biblias, who was one of those who denied Christ, desiring to increase her condemnation through the utterance of blasphemy, brought her again to torture ... she contradicted the blasphemers ... “How” she said, “could those eat children who do not think it lawful to taste the blood even of irrational animals?”

This response bears fascinating parallels to the statement of the aforementioned council of Jewish converts, and is also reminiscent of Moshe’s reply to the Tridentine interrogators that “[i]t is forbidden in the Ten Commandants to kill and Moses [the Prophet] also forbade Jews to eat blood; when they slaughter an animal, they first drain its blood.” To Jews truly innocent of the blood libel, as to early Christians truly innocent of ritual cannibalism, this was a totally reasonable point. There is a single work from 1847—Die Geheimnisse des christlichen Altherthums by Georg Daumer—that argues for the reality of these acts by the Christians, all too predictably ignored by most of the blood libel proponents of its day. But in all likelihood the charges were actually based on pagan misunderstandings of rituals such as the Agape “love feast,” a joyous meal shared between early Christians that culminated in the partaking of the Eucharist—that is, the consumption of the real body and blood of the “son of Man,” a term which in the Greek could plausibly be confused for “child.”

Of course neither this tendency nor these specific archetypes disappeared with the pagans; they would be used recurrently in the later centuries against Christian heretics—mostly pious individuals who disagreed with the Church’s dogmas on certain matters of faith—and in ways even more similar to the eventual blood libel against the Jews. Many of the Church fathers, for example, gave voice to the rumors of certain criminal rites perpetrated by the Montanists. According to Epiphanius, Philastrius, and Augustine, respectively:

People say that at the Easter festival they mix the blood of a child in their offering and send pieces of this offering to their erring and pernicious supporters everywhere

they say some terrible wicked deed is done. For at a certain feast, they pierce a child, just an infant, throughout its whole body with bronze needles and procure its blood for themselves, in their devotion to sacrifice, of course.

[t]hey are said to have polluted sacraments, for they are said to prepare their supposed Eucharist from the blood of a one-year-old infant which they extort from its entire body through minute puncture wounds, mixing it with flour and hence making bread. If the child should die, it is considered among them as a martyr; but if it lives as a great priest.

St John IV, head of the Armenian church, would similarly relate with respect to the Paulicians that “[t]he blood of these infants is mixed with flour to make the Eucharist.” The piercing of young children, the collection of their blood, the mixing with the ceremonial bread—the Eucharist after all being merely the Christian counterpart to matzoh—it’s extremely difficult to dismiss these parallels as purely coincidental, and it’s not too likely such unrelated groups would all arrive at the same specific practice. Certainly, if this is what was being taught and believed about heretics then it’s easy to understand how medieval Christians could find the blood libel against the arch-heretics of their society such a believable theory to draw upon. Far from novel, it was in essence a familiar tool that had arguably been in use for centuries before it was ever applied to the Jews. The blood libel was ultimately, it seems, nothing but a predictable myth created to fulfill the psychological needs of peasants then, just as it’s being revived to fulfill the psychological needs of those modern-day peasants engagement farming on X. ✦

Sources

Ariel Toaff’s Pasque di sangue. Ebrei d'Europa e omicidi rituali; an unofficial English translation can be found on the Internet Archive

Darren O’Brien’s The Pinnacle of Hatred: The Blood Libel and the Jews

EM Rose’s The Murder of William of Norwich: The Origins of the Blood Libel in Medieval Europe

Gavin Langmuir’s Toward a Definition of Antisemitism

Hannah Johnson’s Blood Libel: The Ritual Murder Accusation at the Limit of Jewish History

Israel Yuval’s Two Nations in Your Womb: Perceptions of Jews and Christians in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages

Joshua Trachtenberg’s The Devil and the Jews: The Medieval Conception of the Jew and Its Relation to Modern Anti-Semitism

Norman Cohn’s Europe’s Inner Demons

Ronnie Po-chia Hsia’s The Myth of Ritual Murder: Jews and Magic in Reformation Germany

The Cambridge History of Judaism, VI, p. 57

Sourcing from Resnick’s “Medieval Roots of the Myth of Jewish Male Menstruation,” Chazan’s Medieval Stereotypes and Modern Antisemitism, and Funkenstein’s Perceptions of Jewish History, respectively.

Explored in Blurton’s Inventing William of Norwich

Anglo-Jewish historian Joseph Jacobs was the first to point this out in his 1897 review of the newly-rediscovered Life: “Thorpe Wood is on the opposite side of the town from the Jewry, and to convey the body there the Jews would have had to pass through the whole of the English burg, whereas it would have been much easier for them to have deposited the body in the grove on their side.”

Rose, 18–19.

This list should be comprehensive for the 12th century. Other incidents may have occurred but are now lost to time, yet it's also possible I'm missing some minor reference here or there. Others, like Saragossa (1182), are later inventions. Sources can be difficult, and it's not totally clear whether Bristol (1180; incorrectly 1183), Épernay (1171), or Joinville (1171) even happened.

The one complication is Würzburg (1147) in which the Jews were accused by Crusaders of being responsible for the death of a dismembered Christian man found shortly after Purim. Both the Christian-Latin and Jewish-Hebrew sources describe it as an example of Christian rashness in which 21 Jews were killed, and indeed Crusaders were known to “regard any death on the expedition as a martyrdom, even when it involved no contact with the foe.” Würzburg isn’t included in my list because neither description describes a ritual murder accusation and it’s debated whether it fits the trend; nevertheless an anomalously early Bavarian martyrology from the late 1140s mentions “apud Anglos Willehelmi pueri a Iudeis crucifixi,” demonstrating at least some early dissemination of the Norwich tale into Germany.

See McCulloh (1197)

This is the thesis of Jeremy Cohen's The Friars and the Jews. The Talmud was actually known to Christians before the Disputation, appearing, e.g., in the apostates’ statement or in the writings of Peter the Venerable, but only to a limited extent; see Funkenstein’s “Changes in Christian Anti-Jewish Polemics in the Twelfth Century.”

Langmuir, 270. Also see Hsia, 9 and Yuval, 238.

Some of the sexual accusations against certain heretical sects, like the Gnostic Bogomils their later Cathar descendants, I believe are far more credible than most historians care to admit. These sects taught that reproduction was evil and refused to eat the flesh of anything conceived through sex. (Curiously, they excluded fish from this category.) It seems highly plausible to me that they may have seen anal sex, possibly even homosexual sex, as a lesser evil, or more acceptable way to satisfy one's lust than potentially procreative sex.

An interesting detail for parasceve as a Christian word for Friday/Good Friday is that it it derives from the Greek word for preparation, as in preparation for the Sabbath. It apparently was first used by Greek-speaking Jews.