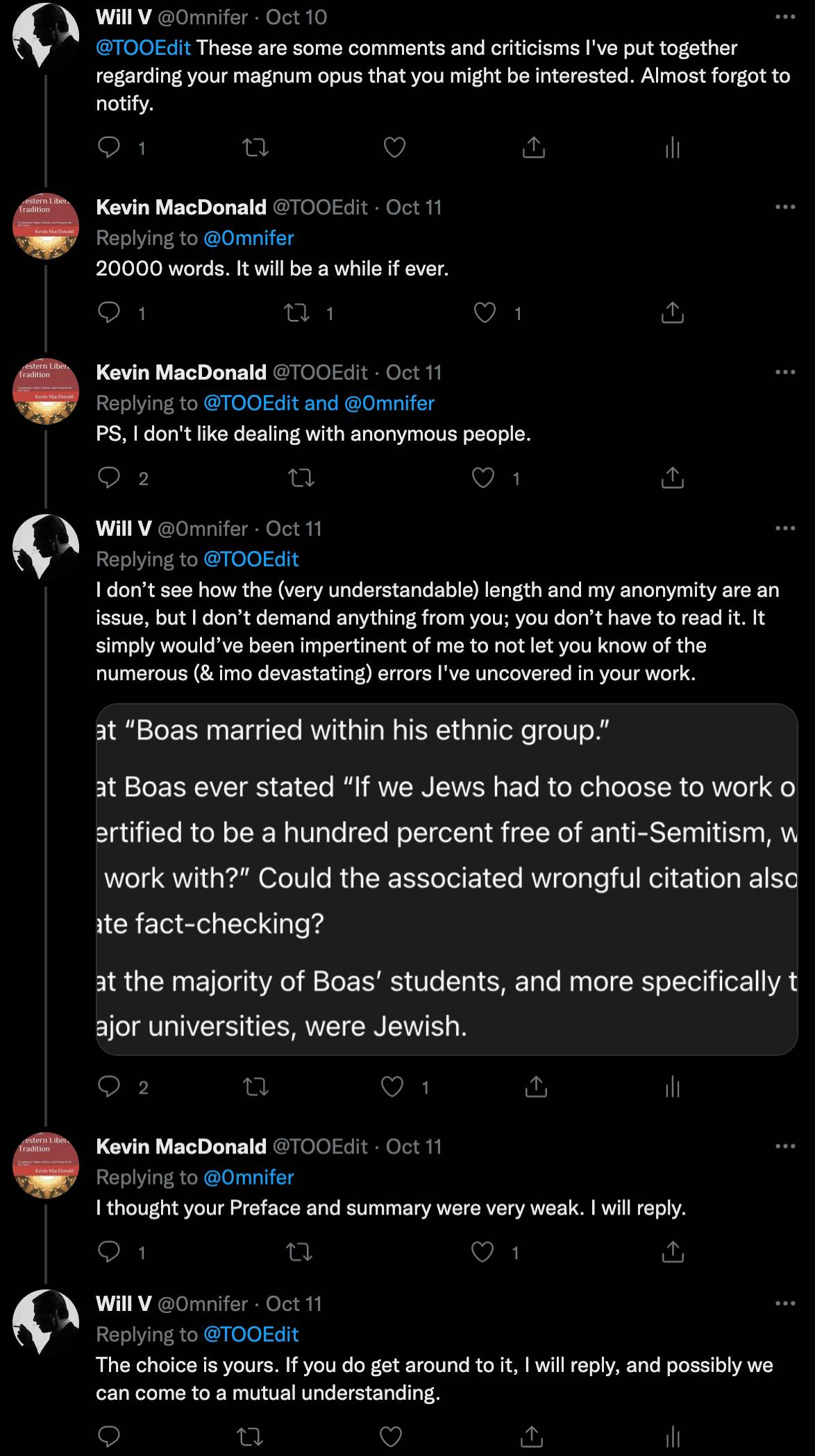

While a continuation of my series of critical responses to Kevin MacDonald’s magnum opus is currently in the works, it will likely be at least a couple weeks before I’m able to publish the next installment. Regarding the previous article on Boasianism, MacDonald is aware of it, and has hesitantly committed to a response (Twitter).

So, we’ll see.

In the interlude, however, is his recent (Oct. 14) publication of a fairly relevant article entitled “Jewish Assimilation?” It’s actually an eleven-paragraph preface to chapter eight of Separation and Its Discontents, the second book in the CofC series. MacDonald does bring up Boas, here, and this article seems to have been written with mine in mind. But who knows for sure.

But if so, he probably still hasn’t gotten around to reading those 20,000 words, because he makes many of the same factual errors in his account of Boas and of assimilation in general, although more reservedly. I’ve decided to briefly analyze this article because it allows me to comment on both subjects.

It begins with the central question: what is specifically meant by Jewish “assimilation”?

I find this to be a pretty semantic topic to dwell on, and one that can be summed up very concisely. Assimilation is a process of becoming — a gradient from totally unassimilated (completely without external influence) to totally assimilated (dissolution of group identity; without distinction from the broader group).1 There is no agreed upon point along this gradient that can satisfactorily be defined as “assimilated.”

What’s relevant to the Jewish Question, however, is one’s degree of Jewish self-identity. Self-defined groups like Jews (or Mexicans, or Lutherans, etc.) by definition have their own set of interests, and as a minority population, these interests will invariably clash to whatever extent with those of the natives. The level of ethnic conflict in these situations is determined by the ethnocentrism of the minority group (their commitment to their own interests) and of the extent of their success and influence which provide the means to effect them. Jews are clearly a very successful group that has engaged in ethnic conflict with surrounding, non-Jewish populations. But the extent of Jewish ethnocentrism, or inversely of the Jewish tendency toward assimilation, is debatable. MacDonald’s contention, naturally, is that Jews are innately a highly ethnocentric group, and this is part of what makes the Jewish strategy unique from any others.

In CofC MacDonald attempts to prove how each major Jewish figure was, one way or another, committed to furthering the Jewish GES through whichever movement they were pioneering. In chapter two, he dedicates a brief section to doing just that with Franz Boas:

Boas was reared in a “Jewish-liberal” family in which the revolutionary ideals of 1848 remained influential. He developed a “left-liberal posture which... is at once scientific and political” (Stocking 1968, 149). Boas married within his ethnic group (Frank 1997, 733) and was intensely concerned with anti-Semitism from an early period in his life (White 1966, 16). Alfred Kroeber (1943, 8) recounted a story “which [Boas] is said to have revealed confidentially but which cannot be vouched for,... that on hearing an anti-Semitic insult in a public cafe, he threw the speaker out of doors, and was challenged. Next morning his adversary offered to apologize; but Boas insisted that the duel be gone through with. Apocryphal or not, the tale absolutely fits the character of the man as we know him in America.” In a comment that says much about Boas’s Jewish identification as well as his view of gentiles, Boas stated in response to a question regarding how he could have professional dealings with anti-Semites such as Charles Davenport, “If we Jews had to choose to work only with Gentiles certified to be a hundred percent free of anti-Semitism, who could we ever really work with?” (in Sorin 1997, 632n9).

But in this article, he emphasizes rather defensively a factor that may countervail against actually proving what he’s supposed to prove.

Jews, as a relatively small minority in the West, must attempt to appeal to non-Jews and avoid framing their theories and policy proposals in terms of their Jewish identity and Jewish interests. Thus one searches in vain for public pronouncements and framing of theories explicitly in terms of advancing Jewish interests. . . . [T]ypically, in the absence of evidence of explicit Jewish activism (e.g., being a member of the ADL or AIPAC), one must must pore over detailed biographies that include, e.g., accounts of private conversations and letters. Freud, for example, left behind a great deal of evidence of his Jewish identity and his sense of Jewish interests. Others did not, so one is forced to piece together an account on relatively scant evidence. . . . [O]ne can be forgiven for pouncing on relatively small indications of Jewish identity and interests as decisive indicators during some periods more than others.

And yet, as I detailed in my last post, MacDonald isn’t merely “pouncing on relatively small indications of Jewish identity and interests as decisive indicators,” but entirely fabricating them. From just the above passage:

Boas never stated “If we Jews had to choose to work only with Gentiles certified to be a hundred percent free of anti-Semitism, who could we ever really work with?” and

Boas did not marry “within his ethnic group.”

As Cofnas (2021) concurs2, throughout the book, MacDonald often will provide very little evidence for a Jew’s ethnocentrism. Speculation about potential motives to conceal all of it also doesn't magically repeal the burden of proof, which rests squarely on MacDonald's shoulders. If the evidence isn't there to prove something, you can't just pretend it's proven and advance an argument upon it, even if you believe it to be true — so much should be obvious.

But it’s certainly true that the appearance of assimilation by a particularly conscientious Jew advancing the GES can be a ruse to suppress suspicions of ulterior motives among gentiles. We cannot, however, use this as a blanket explanation for all the failings of our own evidence. Additionally, signs that one’s assimilation is genuine and not deceptive do exist, and include the following:

A genuine appreciation of the out-group (gentile) culture and community. This is expressed in their personal life, e.g., private correspondence, exogamy, etc.

A lack of much special concern for the in-group to which they apparently belong.

Boas meets both of these criteria very well. He surrounded himself in a thoroughly German environment. He defended the German state when professionally inconvenient. He founded a German cultural society. He was fond of the Kaiser. He married a German Catholic woman. He was never keen to condemn antisemitism. And he encouraged the disappearance of a separate Jewish identity altogether. In Boas’ case we find an extreme example of Jewish assimilation. Yes, to answer the central question, Boas can be described as “assimilated.”

But despite all this, MacDonald maintains that “[i]t’s not too much of a stretch to assume that Boas was ethnically motivated.” Instead of providing independent evidence of Jewishness within Boas, he cites a passage from chapter seven in CofC characterizing Boas’ beliefs, as if beliefs alone can prove the motivations behind them. Instead of proving how Jews like Boas held certain beliefs because of their Jewishness, he circularly asserts (for his very first example in the book, mind you) that they were motivated by their Jewishness because they held those beliefs.

The quote:

Boas was greatly motivated by the immigration issue as it occurred early in the century. Carl Degler (1991, 74) notes that Boas’s professional correspondence “reveals that an important motive behind his famous head-measuring project in 1910 was his strong personal interest in keeping the United States diverse in population.” The study, whose conclusions were placed into the Congressional Record by Representative Emanuel Celler [the Jewish Congressman who was a leader of the anti-restriction forces in the House] during the debate on immigration restriction (Cong. Rec., April 8, 1924, 5915–5916), concluded that the environmental differences consequent to immigration caused differences in head shape. (At the time, head shape as determined by the “cephalic index” was the main measurement used by scientists involved in racial differences research.) Boas argued that his research showed that all foreign groups living in favorable social circumstances had become assimilated to the United States in the sense that their physical measurements converged on the American type. Although he was considerably more circumspect regarding his conclusions in the body of his report (see also Stocking 1968, 178), Boas (1911, 5) stated in his introduction that “all fear of an unfavorable influence of South European immigration upon the body of our people should be dismissed.” As a further indication of Boas’s ideological commitment to the immigration issue, Degler makes the following comment regarding one of Boas’s environmentalist explanations for mental differences between immigrant and native children: “Why Boas chose to advance such an adhoc interpretation is hard to understand until one recognizes his desire to explain in a favorable way the apparent mental backwardness of the immigrant children” (p. 75).

But even here we find mischaracterizations of Degler’s description of Franz Boas. Contrary to MacDonald’s assertions, Boas was primarily concerned with combatting the effects of racism against minority populations, particularly Blacks3, rather than stifling it with diversity. This was likely out of a genuine, liberal concern for the oppressed, the development of which was explained further previously.

To Degler, Boas was not a multiculturalist as MacDonald presents him but an ardent assimilationist, meaning he advocated the total absorption of minority groups into the American national identity, and he viewed his anthropological work on the physical conformity of generations of immigrants as confirming this.

Just a few pages down, Degler clarifies.

George Stocking has described that vision a "melting pot" approach. If that term means the creation of a new culture through the introduction of fresh elements, that does not seem to be quite what Boas had in mind. A more accurate, if less colorful description of his solution to the question of cultural diversity within one country would seem to be "cultural or ethnic disappearance or integration." . . .

His solution, of course, looked forward to the disappearance of Afro-Americans, just as his solution for the differentness of the Amerindians was their ultimate submergence or integration into the general population. He was, in short, no cultural pluralist. Apparently, he even contemplated the disappearance of his own ethnicity. . . .

As the foregoing suggests, it would be a mistake to see Boas as a cultural relativist, that is, someone who saw all cultures as equal, or who refused to recognize a hierarchy among societies. His willingness to see Amerindians and African-Americans integrated into the general American population is only the most obvious evidence of his rejection of cultural relativism. There is, to be sure, no doubt that he repeatedly stressed the necessity of recognizing the value of cultures other than his own, regardless of the degree of differences. Yet, as George Stocking has pointed out, Boas never abandoned the idea that behind all cultures stood a common system of values, especially apparent in the culture of Europeans. Indeed, his basic defense of primitive peoples implied a hierarchy since his invariable point in comparing cultures was that each could potentially achieve the highest culture, which always was Europe's. (80)

This is strikingly at odds with the views of the liberal Jewish organizations MacDonald brings up. I encourage everyone to read this chapter of Degler (1991) for full context, linked here.

MacDonald concludes his thoughts on Boas:

It’s not too much of a stretch to assume that Boas was ethnically motivated along with the mainstream activist Jewish community on this issue. Yet I suspect that if Boas was asked whether his Jewish background influenced his research, he would deny it—something like, “I just think that diversity is intrinsically good. Diversity is our greatest strength.” End of story.

Far from it.

With Boas, we aren’t just taking his word for it, or relying on any superficial displays of assimilation he could’ve been putting on for show. And the question is not whether “his Jewish background influenced his research,” but whether concerns for Jewish interests did. While it’s unlikely they did, if so, it would’ve been a very small motivation among many stronger ones that led him to his ideological convictions, along with numerous gentile acquaintances.

MacDonald is content with simply providing (misconstrued) beliefs of his, and evidence that he was biased to affirm them, as enough of an indication that Boas was secretly a strongly-identified Jew simply hiding all signs of it with an impressive judiciousness and prudence he gave to no other concern of his. But at least MacDonald has now downgraded his certainty from “conclude”4 to a mere “assume.”

From its etymology, we know that “assimilation” is the act of becoming similar. For the concept of cultural assimilation, Oxford Languages suggests “the absorption and integration of people, ideas, or culture into a wider society or culture.”

“In many cases, MacDonald’s evidence that these people were ‘strongly identified’ Jews who ‘saw their work as furthering specific Jewish agendas’ boils down to little more than insinuations based on the fact that they were Jewish and perhaps condemned the Holocaust.“

Page 75: “Nowhere does Boas's commitment to the ideology of equal opportunity and the recognition of the worth of oppressed or ignored people become more evident than in his relation to Afro-Americans“

Culture of Critique, page 23: “I conclude that Boas had a strong Jewish identification and that he was deeply concerned about anti-Semitism. On the basis of the following, it is reasonable to suppose that his concern with anti-Semitism was a major influence in the development of American anthropology.“

Boas' wife was Jewish... here is an article that mentions her father was a prominent surgeon and mentions he is a jew

https://www.google.com/amp/s/forward.com/news/7339/doctors-fill-the-house-at-lenox-hill-s-fantas/%3famp=1